How did the financial crisis of 2008-2009 catch everyone – even the US Federal Reserve – by surprise? And how can economists recognize the next looming crisis before it’s too late?

These questions led Israeli behavioral economist Dan Geller to put a decade of research into developing a scientific prediction tool, the Money Anxiety Index. Over the past three years, many American banks and credit unions have started using the index to predict credit defaults and adjust interest rates.

Geller wrote a 2013 book, Money Anxiety, and a recent study in the Journal of Applied Business and Economics coauthored by Nahum Biger, professor emeritus of financial economics at the University of Haifa.

The Money Anxiety Index uniquely measures financial anxiety based on what people actually do with their money rather than how they respond to surveys about their confidence in the economy.

“When money anxiety is high, people reduce spending one year before they tell about it in response to consumer confidence surveys,” the Jerusalem native says.

This previously unknown factor, he claims, has a major impact on liquidity levels and interest rates in the banking system.

When Geller used his method to analyze historical data from before the 2008 global recession, he saw signs of rising money anxiety as early as October 2006.

Actions speak 12 months earlier than words

“I was amazed that no one saw the last financial crisis coming, and I was determined to find a way to provide the banking system with an early-warning system about the next recession,” Geller tells ISRAEL21c from San Francisco, where he heads Analyticom, a company that provides financial forecasting and analytics services based on the Money Anxiety Index.

“Right around the beginning of the financial crisis, I finished my PhD and had all kinds of tools and an understanding of analytics, and I wondered how so many smart people like the former Fed chairmen Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke missed seeing the Great Recession coming,” he recalls.

“Some of the tools they were using were not conducive to seeing things forward objectively. The ability to see ahead is paramount if we want to keep the banking system safe and stable.”

So Geller put behavioral economics into the equation. Pioneered by Israeli psychologists Dan Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the 1970s, this field studies how people make financial decisions and how they can be helped to avoid mistakes.

“When money anxiety is high, people reduce spending one year before they tell about it in response to consumer confidence surveys.”

“Until the Money Anxiety Index came into existence, the way to measure financial confidence was through questionnaires, like the University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index. It’s very subjective because what people say is not necessarily the same as what they do with their money,” says Geller.

“If we look back at the last few recessions, the lag time between what people do with their money and say they do with their money is on average 12 months. Hence, behavioral economics now has a new principle: Actions speak 12 months earlier than words.”

Two models for banks

Analyticom offers two subscription-based models to US banks and credit unions. Both provide monthly forecasts based on hard data provided by governmental agencies such as the FDIC.

“All the historical data is there, but the predictor is proprietary to us,” Geller explains. “Without the predictor the historical data is useless; it’s like driving while looking in the rearview mirror.”

The first model, Defaults Dynamics, projects an increase in loan defaults about eight months ahead of time, and adjusts the institution’s Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL) – a forecast report mandated by US banking regulations — to reflect an approaching recession.

“For a bank to know, for instance, that mortgage defaults will increase in the next 30 to 90 days is a warning signal. If the increase repeats itself over three months, that is a definite sign the default rate for mortgages is increasing,” says Geller.

“If they’d had these models prior to the 2008-2009 financial crisis, they could have preempted some of the damage done by the real-estate collapse.”

The second model, Deposits Dynamics, allows banks and credit unions to establish optimal interest rates for deposits in the current economy, giving them better control over interest expense and management of liquidity.

No software installation is required, and no sensitive data is transferred.

Geller says each model promises a 98 percent confidence level.

Most clients use both models to manage assets (loans) and liabilities (deposits). Annual subscriptions cost anywhere from $3,600 to $10,000, depending on the institution’s asset size.

“It pays for itself immediately. When you make the right decision on hundreds of millions or billions of dollars, it’s very significant,” Geller points out.

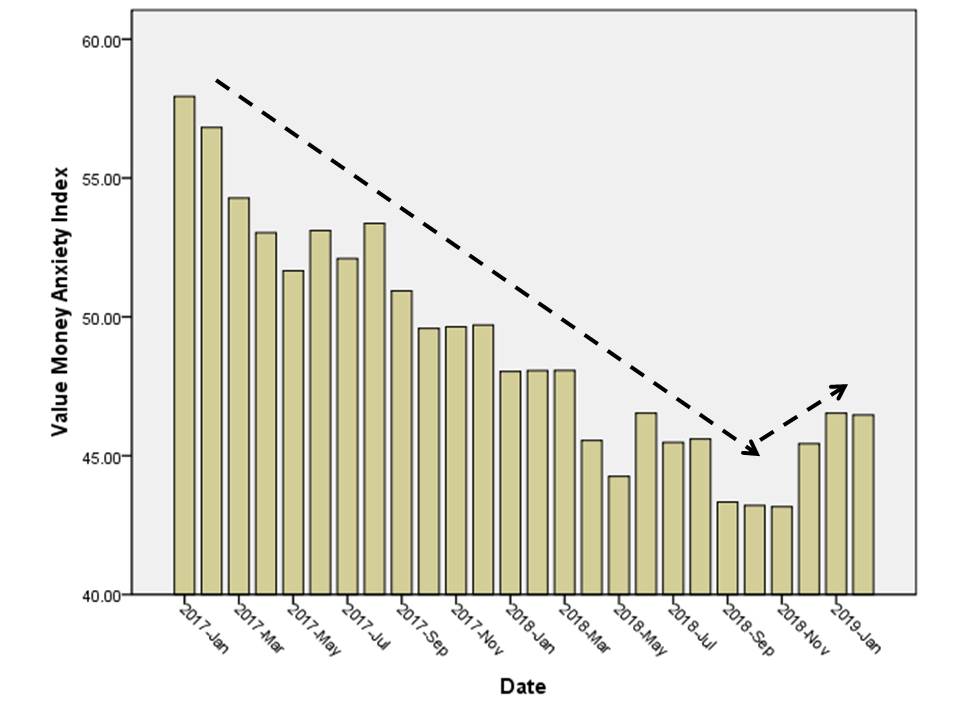

Where does Geller see the economy heading in 2019?

“In the US, we’ve reached the peak of this economic cycle and we are expecting a slowdown relative to 2018, which was a fairly robust economic year. In 2020 we are projecting the beginning of the economic decline and probably the beginning of economic recession at the end of 2020,” Geller tells ISRAEL21c.

However, he adds, “This is part of a normal economic cycle — a normal recession and not a crisis. There is no bubble.”

For more information, click here