Only about 1.2 million of the world’s 400 million ethnic Arabs live in Israel, yet the sole registry for Arab bone marrow donors is located in Jerusalem.

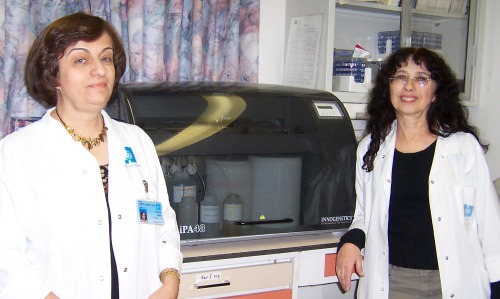

Since 2008, Dr. Amal Bishara has traveled to 60 Arab villages in search of cheek-swab samples for the world’s only Arab bone marrow registry, housed at Jerusalem’s Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center. She has gathered 9,000 samples for the registry, resulting in six life-saving donations.

That might not seem like a lot, considering that about 1.2 million of the world’s roughly 400 million ethnic Arabs live in Israel. But Bishara, who has a Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology from Hadassah, first has to explain the need for a registry of unrelated, anonymous donors. Since Arabs frequently marry relatives, at least 60 percent of those needing marrow find genetic matches within their own extended families.

Using lectures, publicity campaigns, newspaper articles and social media, Bishara has spread the word that the registry is the best means of locating donors for Arabs suffering from blood cancers and a variety of genetic diseases. And her efforts seem to be paying off.

“A small girl needed a transplant recently and our phone did not stop ringing,” Bishara tells ISRAEL21c. “People want to participate. Now my emphasis is on getting university students to join because they are committed, young and healthy.” She’d like to beef up the registry to 50,000 names.

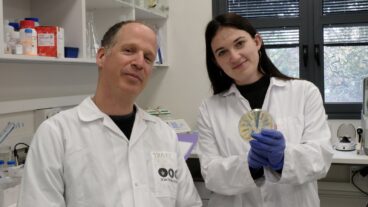

Prof. Chaim Brautbar began Hadassah’s bone marrow registry 22 years ago, and it now includes 75,000 potential Jewish donors. The information is stored in a global registry of about 15 million names, says Dr. Shoshana Israel, head of the registry and Hadassah’s tissue typing laboratory. She says several attempts to convince Arabs to participate had fallen flat until Bishara was brought in.

Donors are angels

“Each ethnic population presents different tissue types, and you have to try to find a population most suitable for each patient,” Israel explains. In the absence of a wide base to choose from among both Jews and Arabs, “the chance of finding donors is very low. So we have to get people aware and tested.”

“We are very excited whenever we find a match,” relates Bishara, who was herself a backup donor for a 24-year-old female patient. “I often accompany donors through the whole process, and it actually changes their lives. One 19-year-old girl said it was the first time she felt she did something good in her life.”

“The donors are really angels,” Israel continues. “Even though it’s not a huge operation, donating is not a trivial thing. Arabs and Jews alike are willing to go through the process just to save the life of someone they don’t know.”

Marrow stem cells today are usually extracted from blood, rather than from bone. After receiving injections to raise their stem cell count, donors are hooked up to an apheresis machine that harvests stem cells as the blood flows from one arm to the other. In cases where actual marrow is needed, it is extracted from a hip bone with a surgical syringe.

Umbilical cord blood registries are also being built up at Hadassah and at Sheba Medical Center from samples banked by the organizations Magen David Adom and Dor Yeshorim, Israel adds.

“If we don’t find a donor from the marrow registry we might do better with cord blood, because it does not require a perfect match. That’s a big advantage for minority populations like the Bedouins, where we don’t have enough donors because we haven’t had the budget to test them.”

A one-woman show

More often than expensive mass recruitment drives, Hadassah puts out calls for donors within the ethnic communities of specific patients. However, general drives would allow for more and faster matching in Israel and other countries where transplants are done.

Bishara runs a virtually one-woman show, and her son or several retired Arab nurses often help with her educational programs and recruitment campaigns. In her presentations, she explains that about 90% of Arab requests for bone marrow transplants are for children with genetic diseases resulting from consanguineous marriages.

“When I explain that because of our unique genetics we only find matches for 10% of the Arab population without a family donor, that convinces people that we need them,” says Bishara. “Once people know [donating] doesn’t harm them, they will be encouraged to join the registry and give a donation if they’re matched.”

All potential donors are made aware that because Arabs and Jews have common ancestors, sometimes an Arab might be a match for a Jew and vice versa. In any case, the identity of the recipient is kept secret. After a year, if the recovered recipient agrees, the donor and recipient are given each other’s contact information.

Hadassah’s was the first Israeli marrow registry, but it is not the biggest – the non-profit Ezer Mizion registry is the largest, with about 500,000 Jewish names. Another small registry is based at Sheba Medical Center, near Tel Aviv.