When describing someone who’s timid or bashful we sometimes use the word “mousy.” However, a new Israeli-German study published in Nature Neuroscience proves that mice – just like people – have quite a range of personalities.

Anybody who’s ever had a pet can testify to the fact that animals have unique personalities. But this is the world’s first set of objective measurements to explore personality in animals.

The method was developed by Prof. Alon Chen and the research groups he heads at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich.

They were hoping to answer some open questions in science about the link between genes and behavior. Perhaps, they reasoned, personality might be the “glue” that binds the two together.

60 observed behaviors lead to personality typing

Personality tests in humans are generally multiple-choice questionnaires. For obvious reasons, that wouldn’t work with mice.

Instead, the researchers videotaped the behavior of color-coded mice over several days in a lab environment.

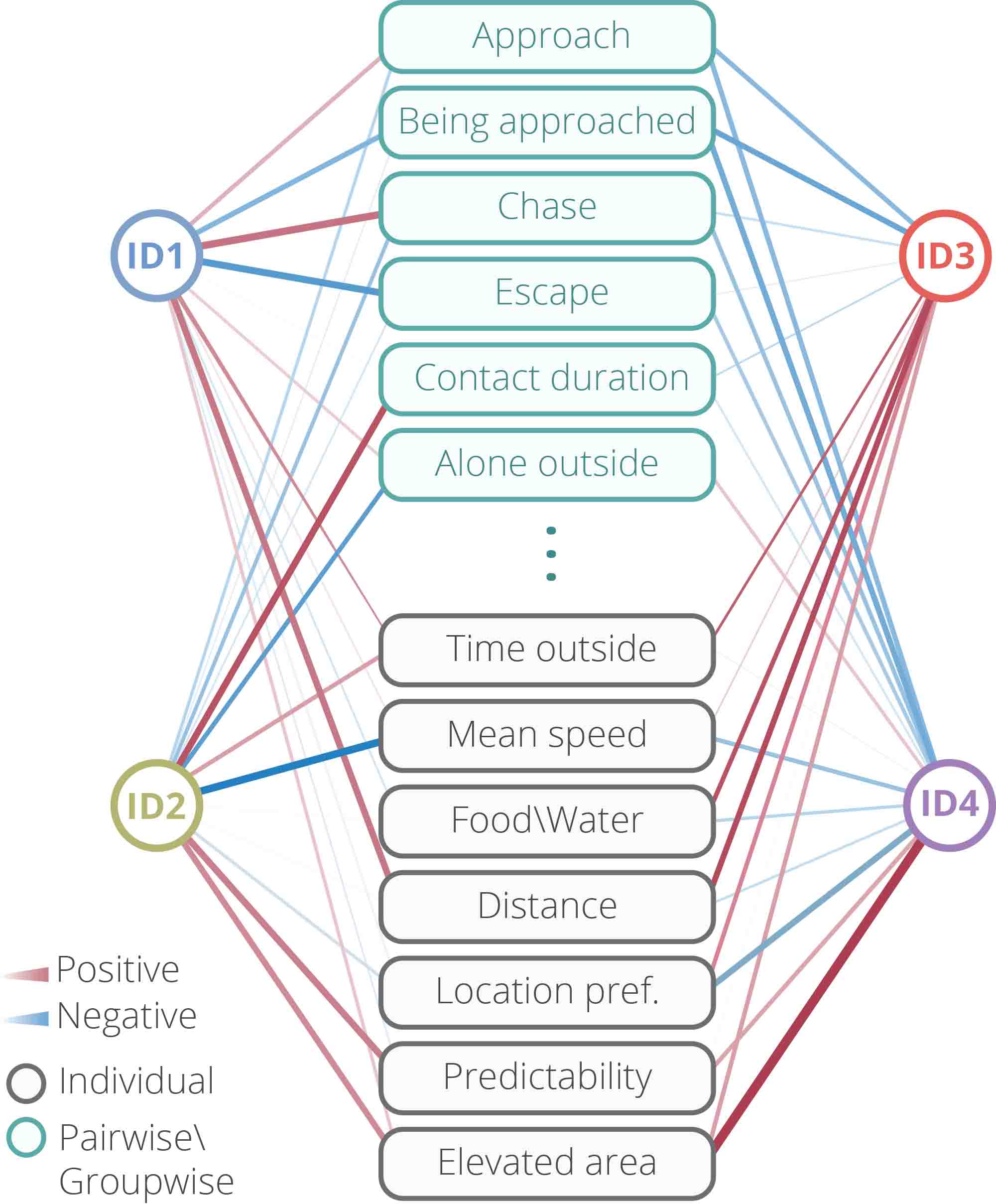

After analyzing the behaviors seen on the video using algorithms written for the experiment, they identified 60 separate behaviors — for example, approaching others, chasing or fleeing, sharing food or keeping others away from food, exploring or hiding.

Next, the scientists wrote a computational algorithm to extract personality traits from the behavioral data.

This resembled the sliding scale used for grading humans on extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness to experience.

When the group assigned the mice personality types based on their scores for four traits, they found that each mouse clearly had a unique, individual personality that consistently informed its behavior.

To see if these traits were stable under different conditions, the researchers stressed the mice by mixing up the groups they were originally tested in. Sure enough, some behaviors changed in the new grouping, but the mice’s personalities remained the same.

Working with Prof. Uri Alon of the Weizmann Institute’s molecular cell biology department, the team plotted out a comparative personality map.

The researchers also mapped gene expression patterns in the brains of the mice. They found that they could identify specific genes associated with certain personality traits they had identified.

Opens the door to many research possibilities

“This method will open doors to all sorts of research,” said Oren Forkosh, then a postdoctoral fellow who led the research in Chen’s group in Germany.

“If we can identify the genetics of personality and how our children inherit certain aspects of their personalities, we might also be able to diagnose and treat problems when these genes go wrong,” said Forkosh.

“We might even, in the future, be able to use these insights to develop more personalized psychiatry — for example, to be able to prescribe the proper treatments for depression. In addition, we can use the method to compare personality across species, and thus to gain insight into the animals that share our world.”

Chen, who is president-elect of the Weizmann Institute, worked on this experiment also with Stoyo Karamihalev, Sergey Anpilov and Yair Shemesh of Weizmann and Max Planck; Markus Nussbaumer, Cornelia Flachskamm and Paul M. Kaplick and Simone Roeh of Max Planck; and Chadi Touma of the University of Osnabrück, Germany.