In Ukraine, it’s considered bad luck to take babies out for a stroll before they’re two weeks old. So when Inna Braverman was born on April 11, 1986, her mother, Ludmilla, waited until April 26 to take Inna for her first carriage ride in Cherkasy, about 200 kilometers from Chernobyl.

That very day, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant had the worst accident in history, releasing 400 times more radiation than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

“My mother always said that the power station got so excited when it saw me the first time that it exploded,” Braverman said with a laugh during a recent interview in her office on the 21st floor overlooking Tel Aviv.

Although she told the story with humor, at the time, Braverman suffered respiratory arrest and was pronounced clinically dead. Her mother, a trained nurse, did mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to save her baby.

“I was given a second chance at life and I always felt I had to do something important,” Braverman recounted.

And so she has. As the CEO of Eco Wave Power, a renewable energy company with a patented technology to generate clean energy from ocean and sea waves, she has received numerous awards, including the United Nations Climate Action Award and the Seal of Excellence from the European Commission.

The company has raised close to $30 million and has wave energy projects around the world.

The power of waves

Because she almost fell victim to nuclear power, Braverman always felt charged with finding alternative power sources.

Growing up in the coastal town of Acre (Akko) in Israel’s Western Galilee, Braverman spent a lot of time on the sea and became fascinated with waves.

At the University of Haifa, she studied political science along with English literature, thinking about going into politics. After graduation, she did translations for a renewable energy company, but she was still thinking about the power of waves.

When she was 23, she met Canadian entrepreneur David Leb at a pool party.

“He asked me, ‘What’s your passion?’ and I told him, ‘Wave energy,’ and he said, ‘Mine, too!’ It was a magical match made in business heaven.”

The two joined forces and began studying companies that had tried to harness the power of waves and convert it into renewable energy.

“We appreciate their efforts because they taught us a lot,” she said. “We wouldn’t have been able to develop our technology without them.”

The main problems of offshore wave energy companies were that the technology was expensive and breakable; nobody would insure it; and environmentalists objected because it created lines in the ocean and sat on the ocean floor.

“I don’t know what this country does to make people believe that they can make it. Even if you’re poor or a woman or without any connections, you believe you can make it. When I’m riding in a taxi in Israel, the driver tells me his idea for a startup. To create this feeling in people is something that is very admirable. I never saw this in other countries.”

“In the past, people interested in wave technology went for larger waves offshore,” she said.

“But every time you want to install or repair the system, you had to go in the water and it is very expensive. There was the case of Pelamis, the famous failure in Scotland. They said they were the future of wave energy and they invested $150 million and the system broke after three days.”

Floaters

After a lot of experiments, Braverman and Leb came up with a pioneering technology using floaters attached to existing structures on land, adding nothing in the water.

“We start with waves that are slower and smaller. The floaters move up and down with the waves, creating pressure that is then transmitted into clean electricity.”

Eco Wave’s first power station was installed in Gibraltar in May 2016, making it the only wave-energy power station in the world.

“We built it for $450,000,” Braverman said. “Nobody believed that it would work and be so cost effective.”

“How did you think you could do it?” I asked.

“When you’re 24, you think you can do anything,” she said. “When you get older, you get disappointed. Bad experiences make us lose our confidence. But influential entrepreneurs all say that no matter how many times you fall, you get up. Your innocence helps you.”

The company began trading publicly on the Stockholm stock exchange on July 18, 2019, and on Nasdaq USA in July 2021.

“We liked that date because the number 18 stands for chai, or life, in Hebrew,” she explained.

“For the American stock exchange, we couldn’t use the letters ECOWAV for our symbol because it was too long. I told my lawyers that my real dream is to have WAVE as our symbol. My lawyers told me I would never, ever get those letters. That night we got a call that WAVE was available. It was very nice.”

Only Israeli company on Swedish stock exchange

Braverman speaks Russian, English and Hebrew fluently – and at breakneck speed. She recently discovered that her lungs aren’t fully developed, a condition that might be linked to the Chernobyl disaster.

“I have to talk fast because I want to make sure I say everything before I have to take my next breath,” Braverman explained.

Chernobyl is not Braverman’s only link to Ukraine, which is now under ferocious attack by Russia. “I still have some family members in Ukraine and my heart goes out to the victims of this difficult situation,” she says.

Though she admits she doesn’t like to comment on political disputes, she believes that this conflict highlights the need for renewable energies.

“The European Union is the largest importer of natural gas in the world, with the largest share of gas coming from Russia (41%). Countries should reach energy independence especially by developing renewable energy projects,” she explains.

It was a gloomy morning when we met and even though she apologized for not feeling well, she seemed animated, filled with enthusiasm for wave energy. She has a magnetic presence, both on and off-screen.

“What does it feel like to be the CEO of a 20-person, multimillion dollar technology company without any engineering experience?” I asked.

“I don’t think I’m luckier than others but I don’t give up on chances,” she said.

She then described how the company became listed on the Swedish stock exchange.

The Founders’ Forum, a worldwide network of leaders in technology, invited her to an event in Tel Aviv. She’d had a bad day and didn’t feel like going, but Leb urged her not to miss the opportunity.

“I was standing there not speaking to any human being in the place, no mixing, no nothing. Then a guy comes to talk to me. I can’t say, ‘No, I’m cranky and I can’t talk.’ So we started to talk and it turned out he was the vice president of the Swedish stock exchange. He invited me to list the company. It wasn’t even on our agenda. But 54% of Sweden’s energy is renewable. So within six months, we were on the Swedish stock exchange. The first, and so far the only, Israeli company.”

Well-heeled instincts

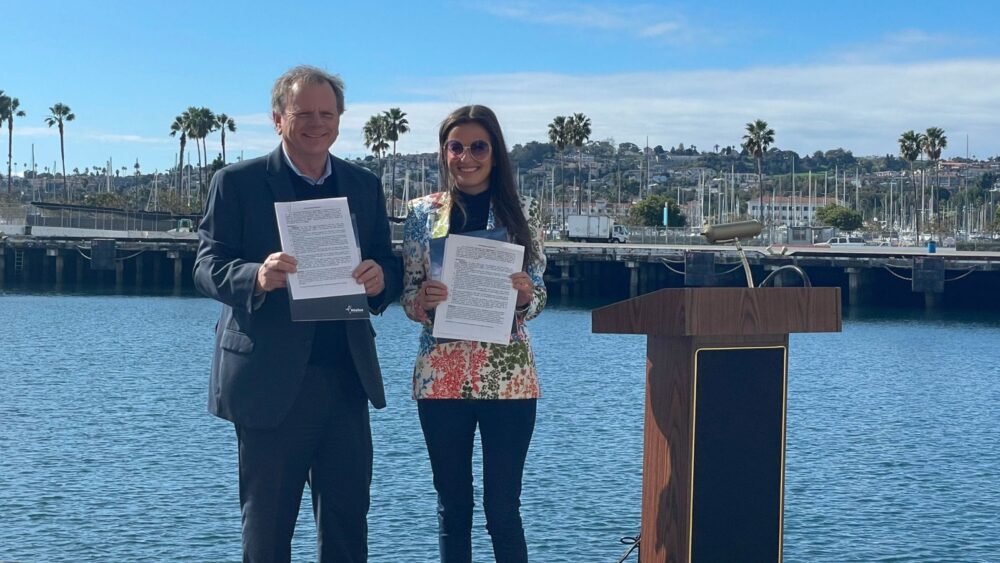

In January, Eco Wave installed floaters on the breakwater in Jaffa Port. The project will begin with providing 100 kilowatts of electricity for 100 houses, with an installed capacity of 100 kilowatts.

Braverman said the Israeli Ministry of Energy, which recognized Eco Wave Power as “pioneering,” has partnered with EDF Renewables IL, a subsidiary of the French National Electric Company, on the project.

Once completed, it will be the first time that wave energy is connected to Israel’s national electric grid. Eventually, the plan is to supply energy to 325,000 households in the Tel Aviv-Jaffa area.

Braverman shared that she has learned a lot in the past 11 years.

“I really trust my instincts,” she said. “In the past, I would see something that I knew was wrong and I would tell the engineers but they’d say, ‘I’m an engineer.’ I’d think, ‘But I am logical.’ Still, I’d agree to their plan and it failed. I’ve learned to trust my own instincts. Experience isn’t always a guarantee.”

Still, it’s hard for her to be a woman in a man’s world. Only five percent of all managerial positions in the technology field are held by women.

“I go to conventions and I’m the only woman. No matter how much you believe in yourself, you’re not taken seriously because you’re a woman. At one of my first meetings, when I was presenting information about the company, one man asked, ‘Can I order an espresso?’ They assumed I was the secretary,” Braverman said.

Today, she says she feels passionate about encouraging other women. “We take a lot of interns and I have a bit of preference in my heart for women. I was at a conference the other day organized by Alliance Global Partners with Israeli women who manage and invest in Israeli companies, trading both in Israel and abroad. There were 16 of us. It was the first time I sat in a room with women. I felt so comfortable. Everyone came out feeling high. Men get that feeling after every meeting and we should, too.”

At the installation at the Jaffa Port, Braverman says, a German TV crew spent at least 10 minutes filming her walking up the industrial steps in her high heels.

She is unapologetically fashionable, writing a post on Facebook declaring, “Women belong everywhere, even on construction sites.”

Braverman said that the first million dollars she raised came from David Leb. “I asked him, ‘Why did you give me money? We’re not family, we’re not related.’ He said, ‘I saw the same spark in you that I saw in myself.’”

Believing you can make it

“A big part of my success is because I’m Israeli,” she admitted. “I don’t know what this country does to make people believe that they can make it. Even if you’re poor or a woman or without any connections, you believe you can make it. When I’m riding in a taxi in Israel, the driver tells me about his idea for a startup. To create this feeling in people is something that is very admirable. I never saw this in other countries.”

She also credits her mother. Her family left Ukraine four years after the Chernobyl explosion, partly because of her and her older sister Nina’s health problems as well as anti-Semitism. The family was well-off and had to sell all their assets back to the government. They arrived in Israel with $300 per person.

“What can you do with $300?” she asked rhetorically. “My father, who was a CEO of a company there, worked in a factory here. My mother, who was not only a nurse but also had a second degree in economics, cleaned houses. One time when I was very little and drawing on the wall, my father came in, very angry, and my mother told him, ‘What are you doing? You’re breaking her spirit. It’s artwork!’ No matter what crazy idea I had, she really believed in me.”

Braverman said that moving here was good for her and Nina, but “my parents paid for it. Now, we can look back and see how hard it was. They put themselves on the line.”

Braverman, who likes playing poker, including Texas Hold ’em, said she appreciates all her parents’ sacrifices.

“My mother now says it was worth it,” Braverman said. “She always tells me, ‘I put all my bets on you.’”