For visitors strolling down the alleys of Jerusalem’s Old City, the sight of the beautifully hand-painted street signs above them is a welcome one. But for Hagop Karakashian it’s also a personal one, and for good reason, too – his father made them.

“I am the third generation of ceramic painters,” he tells ISRAEL21c in a recent Zoom interview. “We are a family of ceramic artists and painters and one of the founders of Armenian pottery in Jerusalem and the Holy Land.”

Softspoken and immensely patient of a last-minute change of plans, Karakashian shares a backstory that encapsulates Middle Eastern history, Jerusalem lore and the diverse communities that make up the city.

His family came to Jerusalem in 1919 from a Turkish town renowned for its Ottoman-style ceramics. The British governor, Sir Ronald Storrs, had invited three artisans to repair and replace the ancient ceramic tiles on the Dome of the Rock.

“They were Mr. David Ohannessian, who was the head of the group — he had ties with the British Mandate and he spoke English very well; Mr. Megerditch Karakashian, who was my grandfather — he was the painter; and Mr. Neshan Balian, the potter — he worked with the clay and made the actual tiles out of the clay,” Karakashian explains.

“On the Temple Mount there was an old kiln. They fixed it and started making the sample tiles for the repair of the Dome of the Rock.”

While the British were pleased with the sample tiles, local Muslim authorities were not happy with the idea of Christians working on one of Islam’s holiest sites.

“The project is cancelled, but the three artists cannot go back to Turkey because of the genocide. They remain in Jerusalem and open together the first Armenian pottery workshop,” Karakashian explains.

Street signs

A few years later, Balian and Karakashian’s grandfather opened a shop on Nablus Road just outside the Old City, where they drew inspiration from ancient local mosaics and painted them on artifacts.

“From 1922 until 1964 they produced mainly beautiful articles like this, and they also did tile work in the Armenian convent, in the Armenian cemetery on Mount Zion and in houses in Katamon [a Jerusalem neighborhood]. They did a lot of tiles. That’s the first generation,” says Karakashian.

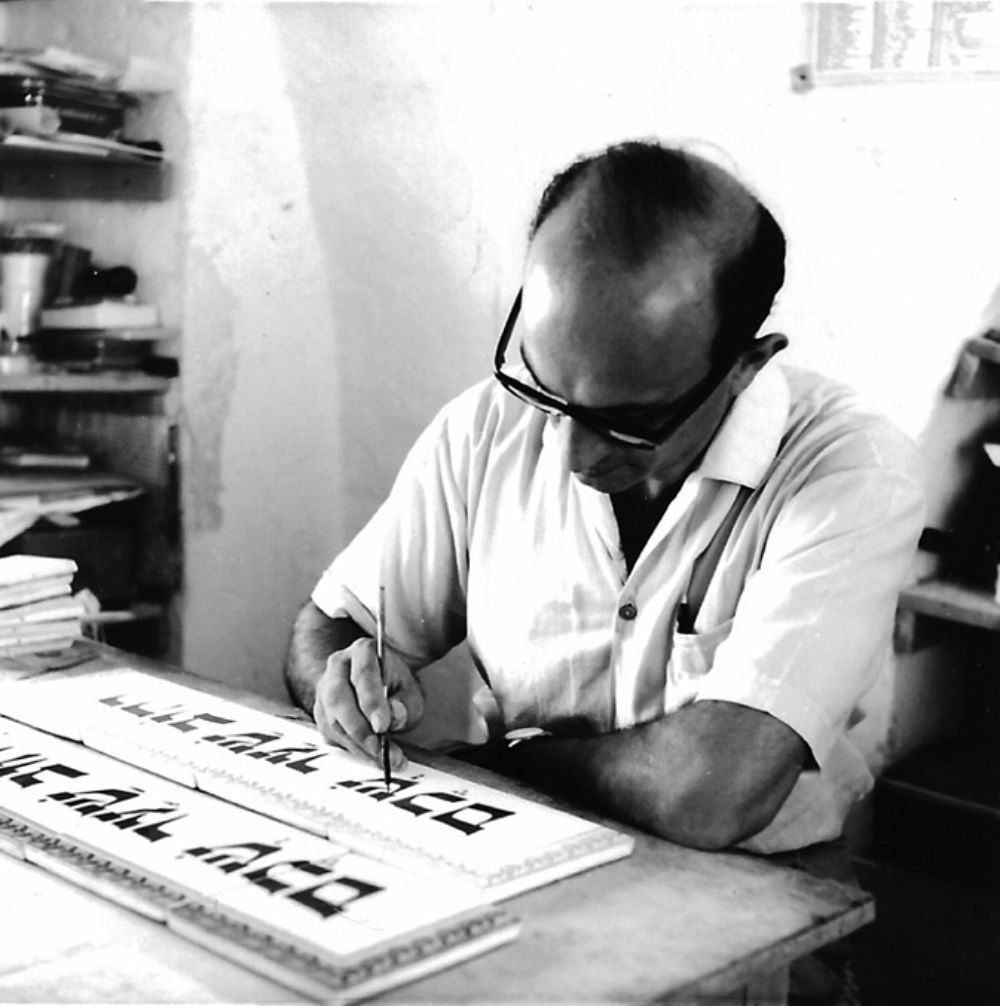

“Now the second generation of Karakashians would be my father. My father and uncle separated from the Balians on Nablus Road and opened a workshop on the Via Dolorosa in the Old City in 1964. The first commission they get is to make the street signs of the Old City. It starts during the [rule of the] Jordanians. The Jordanians asked my father and uncle to do the signs in Arabic and English. They put them up in 1966.”

In 1967, when the Israelis unified Jerusalem following the Six Day War, legendary Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek asked Karakashian’s father to add Hebrew to the street signs.

“If you walk around Jerusalem’s Old City today, you’ll see some of these original signs and you’ll notice that there’s a separating line between the Hebrew and the Arabic and English,” he notes.

“Now every day I walk to work, and I look up at the walls and I see his work there, and it’s very emotional, it’s nice. And here I am, the third generation continuing this family tradition in Jerusalem’s Old City.”

The fourth generation

The family business now includes a fourth generation, as Karakashian’s daughter Patil is learning the craft.

“We do workshops here for people who want to experience Armenian pottery,” he says. “I like to share with people how this art came to Jerusalem, how it is made and how it became a part of the local culture.”

“What’s unique is that before 1919, Armenian pottery did not exist in Jerusalem. It was these three artists who came and introduced and founded this school of art in Jerusalem. Together they brought with them many designs from Turkey.”

Although in Turkey it was forbidden under Islamic law to portray living creatures, Karakashian’s grandfather began adding bird motifs to his creations, particularly peacocks, once he was in Jerusalem.

“In Armenian tradition the peacock symbolizes long life. That’s very symbolic, actually, because not only did these three families survive the Armenian genocide, but this art survived with them when they came to Jerusalem. So a long life is very suitable for what we do.”

He’s still in touch with members of the Ohannessian and Balian families.

“In 1948, because of the war, David Ohannessian left Jerusalem and went to Beirut and stayed there. Members of his family did not continue making this art. But the Balians still work, yes, we still keep in touch. And I keep in touch with Sato Moughalian, the granddaughter of David Ohannessian. She wrote a very nice book about his life recently.”

Only in Jerusalem

The Armenian ceramic art created in the Old City by Karakashian and the third generation of Balians can’t be found anywhere else.

“In Armenia it doesn’t exist; they have a different kind of pottery which is not related to what we do here. In Turkey this kind of art still exists but it’s more Ottoman [style] and that’s why this art is unique to Jerusalem. We take designs from local mosaics, local sources,” Karakashian explains.

“People love it because it’s something very specific to Jerusalem. They also see that it’s still handmade and hand-painted,” he adds.

“In an age of technological progress, people very much appreciate this, especially when you show them how it’s done. They compare what they see in my shop to what they see in the marketplace, which is flooded with wares that are mass produced. Very little of what you see in the market is done by hand. People still appreciate it, that’s why we’re still around.”

This connection between his craft and his city is what keeps Karakashian in Jerusalem even as many members of his community choose to live elsewhere.

“The Armenian community was very large at one point. Armenians had been present in the Holy Land since the 6th or 5th centuries. They came as pilgrims because they were the first nation in 301 AD to accept Christianity as a nation,” he explains.

“In 1915, during the genocide, many people leaving Turkey came here and they found refuge in the Armenian convent, in the Armenian Quarter [of Jerusalem’s Old City]. At one point the Armenian community was maybe 30,000 to 40,000 strong in Jerusalem. Now we number around 1,200, mostly living in the Armenian Quarter.”

He says that difficult conditions in the Old City have led many of the young people to emigrate to Canada, the United States, Australia or Europe. His two sisters live in California.

Those who do stay have been integrating more into Israeli society in recent years, some choosing to do a year of national civil service after high school. Karakashian encourages this trend.

“In general, as an Armenian I mean, we have good relations. We have both Israeli friends and Arab friends; we get along just fine,” he adds. In fact, the Karakashians reside in the largely Arab neighborhood of Beit Tsafafa.

A new business model

Covid has greatly affected the way Karakashian works. Used to selling his wares to international visitors at his Jerusalem Pottery store, he had to adapt to a new reality once Israel’s skies closed.

“Covid did change everything. We learned to survive without tourists. I started doing workshops for Israelis and now I get Israeli groups coming in,” he says.

“I made a lot of friends with Israeli guides who came in and did workshops, and they bring people in. So it’s both fun and it’s a way to survive. It’s a different business model,” he notes.

Those coming to Karakashian’s workshop this time of year will find it fully decorated with his handmade ornaments, ready for Christmas, which Armenians in Jerusalem celebrate later in January than they do in Armenia.

“In Jerusalem it’s celebrated on the 19th. So on the night of the 18th there is a Mass in Bethlehem in the Church of the Nativity,” he explains.

“There’s a practical reason. The Greeks use the Nativity Church for the celebration on the sixth and the seventh, so it’s crowded. We can’t all celebrate at the same time. So they gave Armenians a separate date. This goes back to the Ottomans.”

In the Christmas spirit

In fact, Karakashian’s family celebrates Christmas twice.

“We start celebrating on Christmas eve, the 24th of December actually, because my wife is Armenian Catholic. We go to church and have a family dinner and exchange gifts. We enjoy some of the activities and Christmas bazaars in Jerusalem,” he says.

“One activity is the lighting of the Christmas tree at the New Gate. We also go to the Church of the Nativity for the Armenian Orthodox Christmas prayers on the eve of the 18th of January. Although it’s not an official religious holiday in Israel, we have full religious freedom to celebrate Christmas and pray.”

As our conversation draws to a close, I ask Karakashian if I could attend a workshop, and will it be alright if my two-year-old comes along?

Looking a bit concerned, Karakashian replies with a few questions of his own.

“Well, does she sit? Can she use paint?” he politely inquires. Upon my nodding in the affirmative, he looks somewhat relieved. “Okay, why not.”

Get more information on Jerusalem Pottery and purchasing Hagop Karakashian’s designs here.