For over 40 years, Gideon Shamir, 82, was the only organ builder in Israel. He searched for an apprentice to whom he could pass on his legacy and knowledge, but never found anyone with the patience to do the work.

Then, in June 2021, Shamir took theatre director and playwright Uri Shani, 55, under his wing.

“Uri passed the test with flying colors,” Shamir said. “He grasps what I’m trying to teach, he has good hands and musical ears.”

On February 14, the day I visited Ugavim, Shamir’s organ-building workshop and recital space in Yuvalim, in the Galilee hills, the two men signed a formal agreement. The business is now in the younger man’s hands.

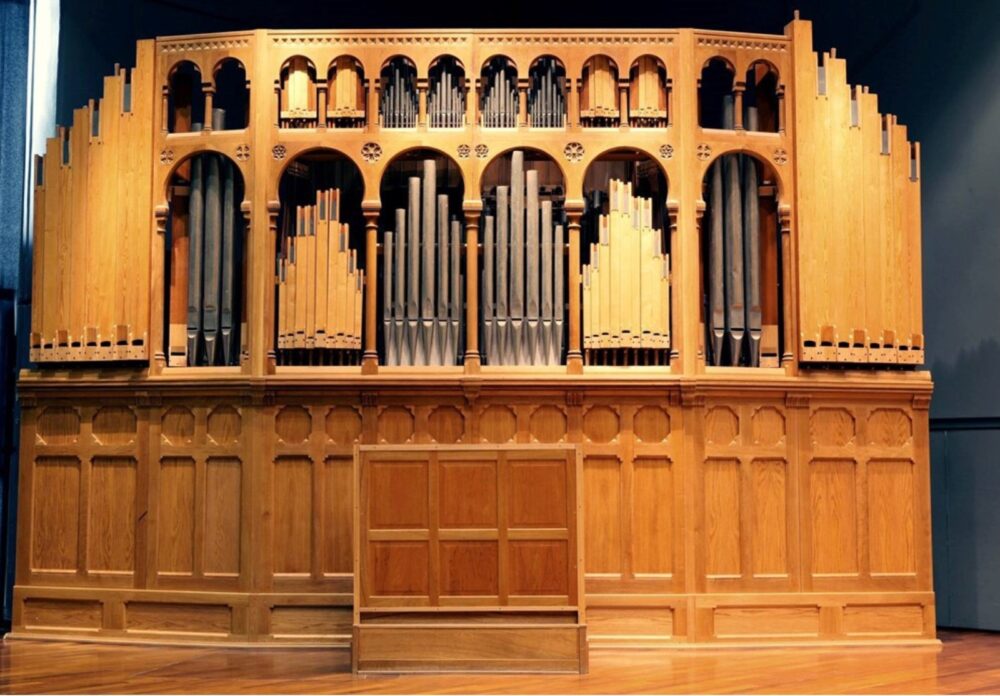

Ugavim’s large, high-ceilinged workshop is filled with metal and wooden organ pipes that soar upwards like mountain peaks.

Before my visit, I knew very little about this musical instrument. I had no idea about the rich history of Jewish organ music.

Shamir points out that the organ is first mentioned in the beginning of the Bible. Genesis 4:21 introduces Yuval, “the father of all who play the harp and the pipe — kinor v’ugav. How fitting that Ugavim (Pipes) is located in Yuvalim.

“There was an organ in the Temple in Jerusalem and few people know there was even an organ in the Great Synagogue in Baghdad,” Shamir says.

An organ is considered the earliest keyboard instrument but works similarly to woodwind instruments because the organist blows air through a hollow pipe into bellows that produce sounds.

“You need a steady wind supply,” Shamir explained.

In the early 1800s, Reform Jews in Germany introduced organs into synagogues. For the next hundred years, Jews created liturgical organ music.

Today, Shani said, there are about 50 organs in Israel, mostly in churches in Bethlehem, Jerusalem and Nazareth. In the 1990s, Shamir built a pipe organ for the Hecht Auditorium in Haifa University. He calls it “the project of a lifetime.”

Fantasy and imagination

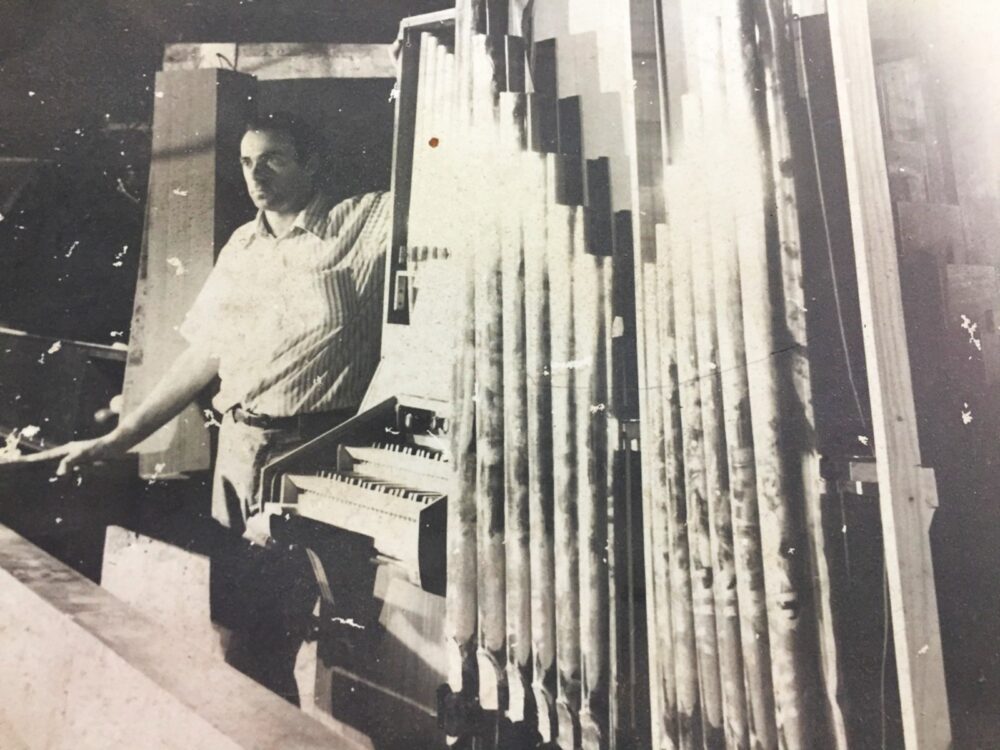

In his twenties, Shamir studied piano at the Royal College of Music in London and won the Queen’s Prize for piano. He then studied organ building in Germany.

Because organs are made mostly of wood, they are affected by climate and humidity, and need maintenance and tuning. (Tuning, Shamir said, is a two-man job.) Shamir makes house calls to restore old organs or to fix broken organs.

“Giving an organ new life is very gratifying,” he said.

Shamir, the elder of the two men, is tall and sometimes stern while Shani is more playful. Working closely together for almost a year, they disagree at times, joke a lot, and often finish each other’s sentences.

To build an organ, Shamir told me, “You need a lot of fantasy and imagination.”

“You have to use chemistry, physics, music and math,” Shani added.

“Less chemistry,” Shamir corrected gently. “But you have to calculate.”

“There’s carpentry, of course,” Shani said.

“And metal and woodworking,” Shamir added, pointing out that it’s a very precise science. A difference in .5 millimeters “may cause trouble.”

At that moment, their lawyer, Yuval Turgeman, walked in with their agreement. The two men signed the papers in moments, without even sitting down.

“How do you think they’ll do?” I asked the lawyer.

“They both have good intentions,” Turgeman said. He then turned to Shani and added, “It’s on your shoulders now.”

“I know I’m stepping into very big shoes,” Shani admits. “I’m not a kid. I’m 55. I know I’m taking a big risk. I see that this is hard work, but I like to work hard.”

He added that everyone who hears about his endeavor with Shamir thinks it’s an excellent match.

Organ-ized

On a tour of the workshop, Shamir and Shani showed me a voice machine which, Shamir said, is the “testing pad” for bellows and pipes. Every organ builder has to have one.

“If he waits to test the organ in church, it will be too late,” Shamir said.

“Oy vey,” Shani said.

“Oy vey is right,” Shamir said.

I followed them into the small carpentry space crowded with dozens of tools. Shani said that when he worked in theater, he made costumes and set designs, and he likes wood-working. When he first came here, however, he had to clean up the place and organize it.

“Organ-ize it?” I repeated, smiling.

He laughed. “I never thought of that.”

Shamir then explained that Shani, who was born in Switzerland, “is very Swiss and likes things to be in order, unlike me.”

“But Gideon’s work is super-accurate,” Shani said.

“And if Uri puts things in order, I can’t find them,” Shamir joked.

The last synagogue organ in Germany

Back in the main workshop space, Shamir turned to me and gestured to two photographs of the same synagogue in Germany. The before and after. Before Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938, when Nazis torched Jewish businesses, schools and synagogues, and afterward when the synagogue was in ruins.

Shamir was born exactly one year later, in Israel. His father had been a commercial artist in Berlin who left for Israel in 1934, the year after Hitler came to power.

Next to the photographs of the synagogue is one of an organ that had been inside the synagogue. Of the hundreds of synagogue organs in Germany, only this one survived — because the synagogue had sold it to a church in 1925. Shamir discovered it in the 1990s.

With Shani’s help, Shamir hopes to bring the organ to Israel and restore it to its original condition. Its pipes had been cut because church music is different.

“There are different sounds,” he explained. “The synagogue organ music mingles better with free singing and a cantor and choir. It’s more mellow.”

Shani’s great-great-grandfather, Jacob Sarasohn, was the chief cantor in a synagogue in a town in Prussia (now in Poland). Sarasohn composed liturgical music and his daughter (Shani’s great-grandmother) was part of the girls’ choir in the synagogue, which was destroyed in the Holocaust.

Shani, who has played piano since he was seven years old and has started to play the organ, has been trying to find some of Sarasohn’s music compositions.

“We had this incredible culture of organ music in Judaism and we lost it,” Shani said. “It’s part of Jewish tradition.”

Shamir also wants to revive the rich tradition of synagogue organ music. Although playing musical instruments is prohibited on the Sabbath in Orthodox practice, the organ could be played on other holidays, like Hanukkah, and at weddings.

“People can write new liturgy and perform new music,” Shamir suggested.

Time to get to work

I asked each man what he wanted to say to the other at the start of their formalized agreement.

“Uri, I’m not leaving you on your own,” Shamir said. “I want you to succeed. I want you to be happy so I can be happy. I want to have my own time. I’ve had enough.”

“I’m saying thank you, a big thank you, for choosing me,” Shani told him.

“Don’t be too sentimental,” Shamir said. “Now we have to roll up our sleeves and get to work.”

Ugavim holds organ recitals and workshops, including a workshop for children where they will build their own organs out of kits. For further information, click here or call 972-52-331-7154.