If administered in the early-onset stages of the disorder, drugs used to treat schizophrenia may have the power to prevent it, according to Israeli researchers.

New research from Israel suggests that it may be possible to prevent schizophrenia if it can be caught before it fully manifests itself. The study, from Tel Aviv University (TAU), shows that early intervention could prevent the mind-altering disorder.

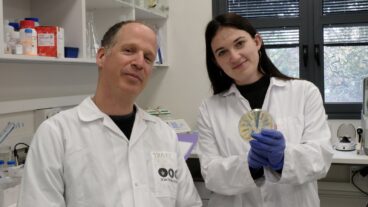

Prof. Ina Weiner of the department of psychology at TAU says: “The big question asked in recent years is if schizophrenia can be prevented.” Her response is that drugs like clozapine that are used to treat schizophrenia might, if administered during a subject’s adolescence, prevent the development of the disease in those predisposed to it. “Pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia remain unsatisfactory, so clinicians and researchers like myself have started to dig in another direction,” she says. Their results provide hope.

The onset of schizophrenia, which affects about 1.1 percent of the US population, is not easy to predict. Although it is associated with as many as 14 genes in the human genome, the prior presence of schizophrenia in the family is not enough to determine whether one will succumb to the mind-altering condition. The disease also has a significant environmental link.

Searching for biological cues prior to onset

Weiner explains that the developmental disorder, which usually manifests in early adulthood, can be triggered in the womb by an infection. But unlike developmental disorders such as autism, it takes many years for the symptoms of schizophrenia to develop.

In their study, recently reported in Biological Psychiatry, Weiner and her colleagues Dr. Yael Piontkewiz and Dr. Yaniv Assaf sought to discover biological cues that would help to trace the progression of the disease before symptoms manifested. “If progressive brain changes occur as schizophrenia is emerging, it is possible that these changes could be prevented by early intervention,” she says. “That would revolutionize the treatment of the disorder.

“We wondered if we could use neuro-imaging to track any early-onset changes in the brains of laboratory animals,” Weiner relates. Then she says, the scientists asked: “If so, could these changes and their accompanying schizophrenia-like symptoms be prevented, if caught early enough?”

Weiner and her team gave pregnant rats a viral mimic known to induce a schizophrenia-like behavioral disorder in offspring. This method simulates maternal infection in pregnancy, which is a well-known risk factor for schizophrenia. Weiner demonstrated that the rat offspring were normal at birth and during adolescence. But in early adulthood, the animals, like their human counterparts, began to show schizophrenia-like symptoms.

Arresting brain deterioration

As she examined brain scans and behavior, Weiner found abnormal development of the lateral ventricles and the hippocampus in those rats with “schizophrenia.” Those that were at high risk for the condition could be given drugs to treat their brains, she determined.

Following treatment with risperidone and clozapine, two commonly used drugs to treat schizophrenia, brain scans performed at the Center for Computational Neuro-Imaging at TAU showed that the lateral ventricles and the hippocampus regained a healthy size.

“Clinicians have suspected that these drugs can be used to prevent the onset of schizophrenia, but this is the first demonstration that such a treatment can arrest the development of brain deterioration,” Weiner says, adding that the drugs work best when delivered during the rats’ “adolescent” period, several months before they reach full maturity.

Currently, anti-psychotics are prescribed only when symptoms are present. Weiner and her colleagues believe that an effective non-invasive prediction method (following the developmental trajectory of specific changes in the brain), coupled with a low dose drug taken during adolescence, could stave off schizophrenia in those most at risk.

Weiner has already begun research to determine the point at which changes in the brain can be detected.

Estrogen as ammo against schizophrenia

In a related development, Weiner has also discovered that the female hormone estrogen may work as a protective agent in menopausal women vulnerable to schizophrenia.

While estrogen replacement therapy has long been a controversial treatment for the symptoms of menopause, a TAU study shows that it may have a positive effect in women who are at risk for schizophrenia.

“Antipsychotic drugs are less effective during low periods of estrogen in the body, after birth and in menopause. Now our pre-clinical findings show why this might be happening,” says Weiner. “Our research links schizophrenia and its treatment to estrogen levels.”

Weiner and her doctoral student Michal Arad have reported findings suggesting that restoring normal levels of estrogen may work as a protective agent in menopausal women vulnerable to schizophrenia.

Their work, based on an animal model of menopausal psychosis, was recently reported in the journal Psychopharmacology. In their study, Weiner and Arad removed the ovaries of female rats to induce menopause-like low levels of estrogen and showed that this led to schizophrenia-like behavior. The researchers then tried to eliminate this abnormal behavior with an estrogen replacement treatment or with the antipsychotic drug haloperidol.

Estrogen replacement therapy effectively alleviated schizophrenia-like behavior but haloperidol had no effect on its own. Haloperidol regained its effect in these rats when supplemented by estrogen.