Perhaps harking back to biblical times, or resonating with Israel’s interest in growing crops in the desert, Israeli scientists have cultivated what they believe to be the world’s best pasta wheat. It’s touted as having the best nutritional quality, yield, pest-protection and physical properties of durum that you need to make pasta. And it’s best grown in Israel.

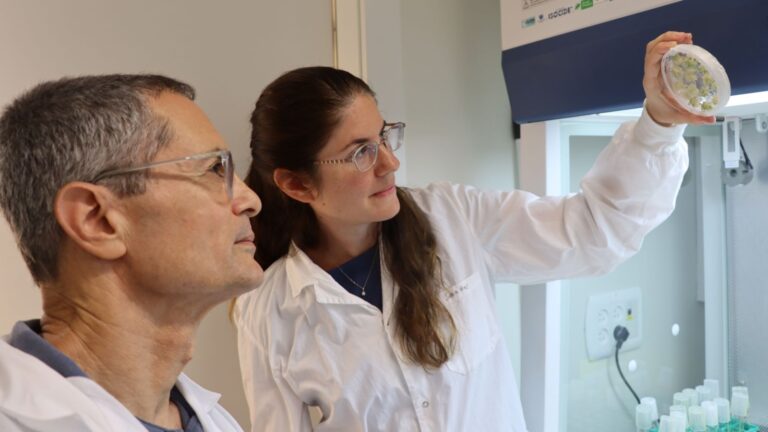

While taste is very much a personal sense, the Israeli research project, headed by Dr. Uri Kushnir from the department of plant sciences at Israel’s government-run Agricultural Research Organization-Volcani Center, has pleased the taste buds of some of Europe’s most discerning pasta experts in Italy and Switzerland.

“It’s a high-quality wheat nutritionally and pathologically — being insect-resistant and pest-resistant,” says Kushnir, who has created three cultivars and named each one after an Israeli agricultural hero. He notes that all three were developed by non-GMO (genetically modified organism) means, using a Japanese technology, and are very high in protein. They show high levels of resistance to wheat pathogens such as yellow rust fungus, a common problem for durum growers. Durum is the wheat of choice for pasta flour.

Developed from three varieties of wheat, an ancient wheat from the Middle East called emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum), known as farro in Italy, a modern Israeli cultivar and one from Arizona in the United States, the new genetically superior durum technology offers the best that all three have to offer.

From the mother of all wheat

“I transferred genes from the [ancient] wild wheat of Israel – wild emmer being the ancestor of all cultivated wheat. From 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, human beings started to select them and later cultivate them by domestication,” Kushnir tells ISRAEL21c.

In addition to boasting superior nutritional qualities and environmental benefits, at 6.6 tons per hectare his new cultivar yields have surpassed those of one of the world’s primary durum cultivars from Arizona, he relates.

Durum wheat, unlike wheat used for bread, needs to exhibit special basic qualities to be suitable for pasta making, Kushnir explains. “Durum needs specific traits,” he says, listing high protein content, a high wet gluten content to make the pasta dough flexible, and most importantly, the yellow color of the wheat. Not all wheat makes the grade, and not all wheat-growing areas can produce a good durum.

According to Kushnir, Israel, neighboring countries, and the Mediterranean region at large are eminently suitable for durum wheat production. He would like to see Israel become a major exporter of his new wheat varieties named Gvati, Uzan (both Haim Gvati and Aharon Uzan were agriculture ministers), and Eliav (after Arie ‘Lova’ Eliav, one of the pioneers of the Israeli settlement movement who died this year).

“We’ve received very high compliments on its quality,” says Kushnir, adding that “Israel is one of the countries in the world where durum wheat is suited to grow. It has limited growing areas, needing high temperatures.”

While Kushnir imagines that Italy will be a major customer for the new wheat, Saskatchewan in Canada and North Dakota in the US are other regions that could import the Israeli-raised cultivars developed using a special technology invented in Japan called double haploid production. It allows researchers to do Mendel-like plant experiments within a year instead of a decade.

Canada recently claimed it was the first to derive new varieties of durum wheat using double haploid technology, but Kushnir wants to set the record straight: His lab already saw results back in 2005, he told the Canadians to their dismay.

The researchers have also developed a new variety of bread wheat flour, which promises all the nutritional benefits of whole wheat bread but which looks and tastes like white bread. Named Barnir, the wheat can be grown in dry and irrigated regions and could alleviate diabetes since it absorbs sugar more slowly, asserts Kushnir who claims it’s healthier than rice.

And while Israel still imports a majority of its wheat for bread making from the US, historically wheat has a very special relationship to Israel and the Middle East. The ancient emmer wheat is believed to have contributed to the development of modern civilization, allowing people to work the land and create settlements and societies.

Wheat of peace?

Back in biblical times, more than 2,000 years ago, the wheat grown in Canaan [ancient Israel] was durum wheat and there are biblical references to prove it, says Kushnir.

What’s considered ‘cheap’ durum today, a rough ground grain called semolina, was once the food for the land of Canaan’s A-listers. The Hebrew word ‘solet‘ and the Hebrew expression from Aramaic “shamna ve salta” translates to “oil and semolina” and is used to describe the cream of the crop of society.

Kushnir’s new wheat species may also contribute to peace in the Middle East, he suggests. A popular Arab grain called freekeh, based on durum, is produced in Syria. Eaten like rice or couscous, the heads of wheat from the durum are burned when they are still green, releasing a strong, smoky flavor. Kushnir says there are biblical and other ancient references to freekeh as well, and that it was the ingredient in lechem kali, a roasted bread.

Syria, he agrees, is also a good place to grow durum, noting that the Syrians are already producing and exporting this special product. Some cross-fertilization with durum seeds from Israel could help the region to plant some much-needed wheat of peace.