Changing the gut microbiome can reprogram the immune system to attack malignant tumors, according to results of a unique clinical trial at Sheba Medical Center in Israel.

The results were published in the peer-reviewed journal Science by a research team led by senior GI oncologist Dr. Ben Boursi, senior oncologist Dr. Gal Markel and MD-PhD student Erez Baruch.

“For the first time in the world, we have successfully fought cancerous tumors by changing the gut microbiome,” Boursi said.

“Currently, immunotherapy works for only 40 percent to 50 percent of patients. We anticipate that with the help of this revolutionary treatment, we will see as many patients as possible transforming from non-responders to responders,” he said.

The researchers performed fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) on 10 terminally ill patients with metastatic melanoma who had not responded to immunotherapy and had exhausted all other existing treatment options.

“In the first stage, we eradicated the patient’s existing microbiome, after which we transplanted gut microbiota from cancer survivors who’d had melanoma, but who had responded well to immunotherapy and who had been cancer-free for at least one year,” Boursi explained.

Significant results

Two weeks after the donor microbiome was introduced via colonoscopy, and the patients had completely absorbed the donor microbiota, they resumed immunotherapy.

They also received odorless, flavorless pills containing the same bacteria for three months.

In two of the study participants, tumors shrank considerably. One patient’s tumor disappeared and hasn’t returned even more than two years later.

“To see a 30 percent response is really extraordinary,” Boursi explained to ISRAEL21c, considering the terminal condition of the participants and their previous failed treatments.

Most significantly, Boursi and his team saw evidence of an increased immune response on the cellular level as well as in gene expression profiles of the three patients who did respond well.

He believes that some of the transplanted patients weren’t responsive to the immunotherapy due to genetic changes in their tumors – meaning the microbiome is not the only factor that can affect the response to treatment.

“Although we emphasize the clinical benefit of the treatment, we should remember that it is the cherry on top,” he said. “Our main goal was to see if the treatment is safe and feasible.”

Now that the microbiome transplant procedure has indeed been shown to be “simple, safe and relatively inexpensive,” Boursi and the team at Sheba are testing it on other melanoma patients as well as patients with lung cancer, one of the most common causes of cancer death.

Side effects disappeared

Regardless of whether or not the FMT affected the success of immunotherapy, it had another unexpected benefit: While many of the trial participants had suffered severe side effects during their earlier failed round of immunotherapy, after the FMTimmunotherapy caused no significant side effects at all.

“This alone is a tremendous achievement,” said Boursi.

Now the team is exploring whether the transplant treatment could be used specifically to help ease immunotherapy side effects.

They anticipate that their continued lab work may help them identify cancer patients who will benefit most from FMT therapy, as well as identify the most appropriate donor for each patient.

They also hope to define the biological pathway underlying the change in immune responsiveness.

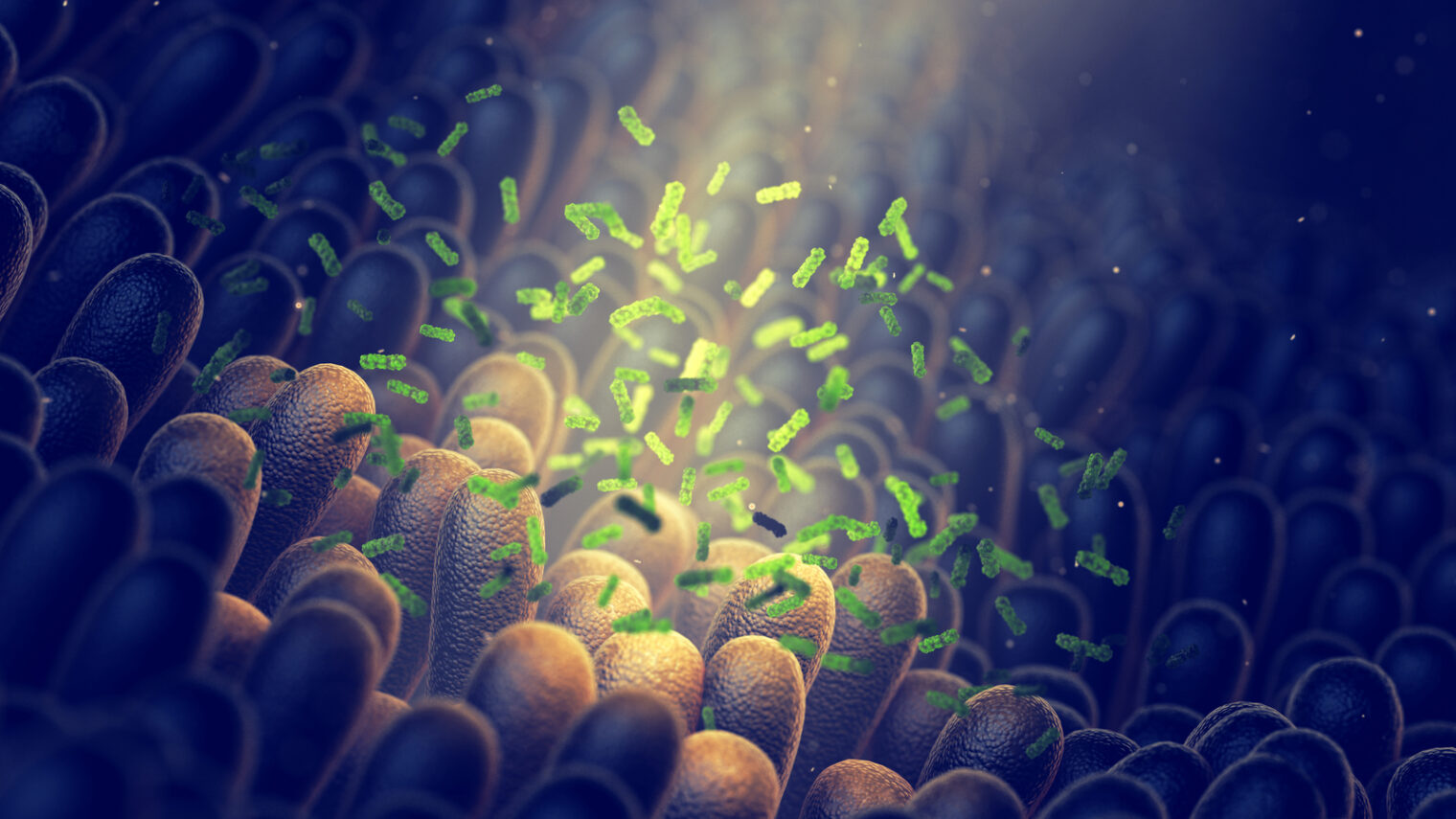

What is it about the gut microbiome that can make such a difference in the success of immunotherapy?

“We know that the gut microbiome has many roles in human health, and one is the development of the immune system,” Boursi tells ISRAEL21c. “For example, in germ-free mice the immune system does not develop properly.”

Other authors of the study are affiliated with Tel Aviv University, Shamir Medical Center, Hadassah Medical Center, Bar-Ilan University and Assuta Ashdod University Hospital, all in Israel; and with the University of Pennsylvania and University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in the United States.