Israeli researchers have discovered that studying micro-climates could help farmers worldwide dramatically increase their yields.

Hikers and nature lovers can feel the landscape through which they tread: Lower in the valley, the moist, cool air offers a reprieve on a sunny summer day. The footpath around the mountain is drier, noticeably warmer. What they are experiencing is topoclimates, or micro-climates.

You won’t find this kind of information on modern weather maps, which generalize and average out temperatures in specific locales over hundreds of miles, blurring the details of variable climatic conditions in each small area.

According to new research from Israel, if farmers had access to such precise data, they could better time sowing and harvesting, predict how much water might be needed that year to water the crops, identify parts of a field that may be more cool, humid or prone to dry, hot winds — and potentially avoid devastating damage by pests, perhaps using less pesticide as a consequence.

A team of researchers led by Itamar Lensky from Bar-Ilan University and Uri Dayan from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem are providing just this kind of information to Israeli farmers, for the first time, using public satellite data collected by NASA on microclimates throughout the world.

First survey of the Holy Land

By next year, the team hopes to have a detailed map of the microclimates of Israel.

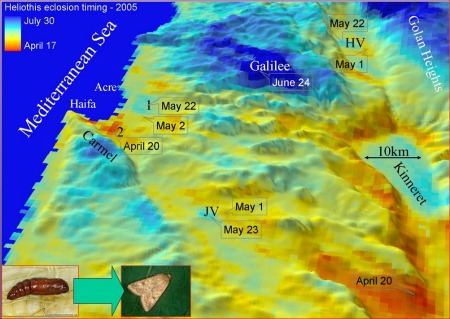

Lensky explains this in his paper published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. Looking at corn crops, he surveyed three different valleys all within a short distance of each other. “I fed into my computer the whole northern part of Israel planted with corn in March and then I waited for 120 days and looked at what is the expected height at each point at very short distances from each other.”

Remarkably, even on farms in the same vicinity, the height of the stalks can be radically different. In one field, the stalks were 40 centimeters (nearly 16 inches) higher in a plot that was planted at the same time as two others.

Microclimate data could help farmers know where and when to plant to improve yields. One tract of farmland could be sowed earlier and another later, depending on the varying temperatures. This sort of information may be increasingly meaningful as natural resources become more stretched, and countries fight to increase yields to the maximum.

And as climate change effects become more severe, access to this data could be even more crucial in the area of pest control.

“Insects and other cold-blooded animals depend on ambient temperature for development,” Lensky tells ISRAEL21c. “We showed with corn and heliothis, an insect that feeds on corn, tomatoes and cotton — and many different plants all over the world — the effect of local climate on the plants and also on the pests.”

An e-almanac for farmers

A difference of a few weeks can make or break a season’s harvest. If the pests emerge when the crop is ripe for the eating, severe damage may be done. But with smart maps, farmers can determine when to plant to avoid pest damage. And better still, Lensky reasons, farmers might collaborate, working together on a regional basis for pest control.

According to Lensky, the raw data he used in his study is freely available to the public by way of NASA’s Terra satellite, launched about 10 years ago to track the world’s changing climate.

But on its own, the NASA data doesn’t mean much, adds Lensky. The physics and atmospheric science researcher, who also works in the Dead Sea region and other environmental projects, says that sometime next year he hopes a model will be made to help farmers throughout Israel.

In the foreseeable future, such microclimate models could be made for farmers around the world, giving detailed information about each square mile — an electronic farmer’s almanac, if you will.

“To apply this to other places isn’t easy. But the [model] could be integrated and used by scouts and decision-makers,” Lensky concludes.