The happy month of Adar is here, bringing with it warmer weather and the Purim holiday. The cacophony surrounding Purim — costumes and masks, cakes and candies, music and parties, wine, spirits and general gaiety — is sometimes so loud we forget what we’re actually celebrating. So here it is: Purim commemorates the deliverance of the Jews living ancient Persia after a plot to destroy them was uncovered and the Jews given license to defend themselves.

Or, as the joke goes, they tried to kill us. They succeeded. Let’s fast. They tried to kill us. They failed. Let’s eat.

The historicity of the Purim story in the Book of Esther is debatable; there are elements in the Book of Esther that are historically accurate and others that are questionable, including the lead characters Queen Esther, her cousin Mordechai, the evil vizir Haman and even King Ahasuerus, who may or may not have been the historical Xerxes… or perhaps King Artaxerxes I… or King Artaxerxes II.

What is for certain is that, over the centuries, the holiday evolved and borrowed elements from other spring festival traditions. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, the custom of dressing in costume, “was first introduced among the Italian Jews about the close of the fifteenth century under the influence of the Roman carnival. From Italy this custom spread over all countries where Jews lived, except perhaps the Orient… Purim songs have even been introduced into the synagogue…As early as the fifth century… and especially in the geonic period (9th and 10th cent.), it was a custom to burn Haman in effigy on Purim”.

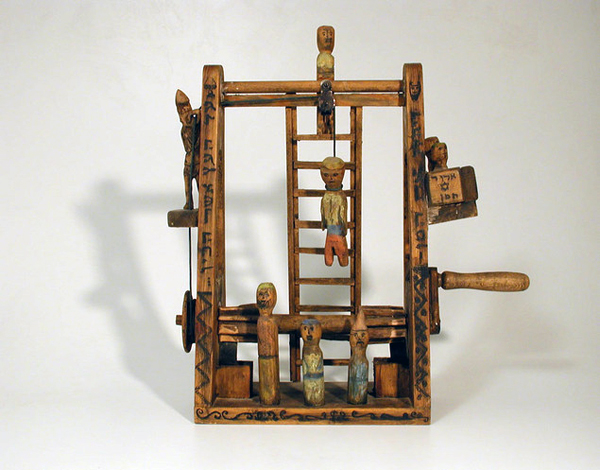

Hangman noisemaker by Zion Drori (1978). Wolfson Museum at Hechal-Shlomo

Then there’s the noise-making. “Purim was an occasion on which much joyous license was permitted even within the walls of the synagogue itself. As such may be reckoned the boisterous hissing, stamping, and rattling, during the public service, at the mention of Haman or his sons, as well as the whistling at the mention of Mordecai by the reader of the Megillah. This practice traces its origin to French and German rabbis of the thirteenth century, who, in accordance with a passage in the Midrash, where the verse ‘Thou shalt blot out the remembrance of Amalek’ (Deut. xxv. 19)… introduced the custom of writing the name of Haman, the offspring of Amalek, on two smooth stones and of knocking or rubbing them constantly until the name was blotted out. Ultimately, however, the stones fell into disuse, the knocking alone remaining”.

“Some wrote the name of Haman on the soles of their shoes, and at the mention of the name stamped with their feet as a sign of contempt; others used for the same purpose a rattle, called ‘gregar’ (= Polish, ‘grzégarz’), and producing much noise…”

The Sir Isaac and Lady Edith Wolfson Museum at Hechal-Shlomo – The Jewish Heritage Center in Jerusalem has a lovely collection of Purim noisemakers from the collection of Prof. Daniel Sperber. These range from the 18th century “hammer”…

To the 19th century “clapper” — available today in colorful plastic…

This “hammer”style noisemaker was fashioned in 1947 at a Cyprus internment camp after World War 2. It is decorated with a 1933 German coin and the carved swastika is engraved with the words “And they hanged / Haman”.

The wonderful Nostal.co.il site also has holiday noisemakers on display, like this 20th century tin “gragger”…

And Judaica artisans Agayof have produced a modern take on the traditional noisemaker: a proud Lion of Judah, symbol of Jewish strength and of Purim’s underlying theme: Never again!