Israel’s Bedouin community has undergone major shifts in the past decades, transforming from a nomadic people into a more modern one complete with town dwelling, formal education and technology.

But this change came with the danger that the ancient Bedouin traditions could become completely forgotten with the passage of time.

Luckily, a new collection in the works at the National Library of Israel preserves 50-odd years of documentation of the Bedouin community carried out by a world-renowned expert. It will be made freely available online within the next year.

The collection will be based on the archives of Clinton Bailey, a US-born Israeli Middle East expert who for 50 years collected materials from the last Bedouin generation to grow up in the pre-modern period, making them an invaluable source of an orally transmitted ancient civilization.

Bailey first came across the Bedouin when he was working as an English teacher in the Negev Desert.

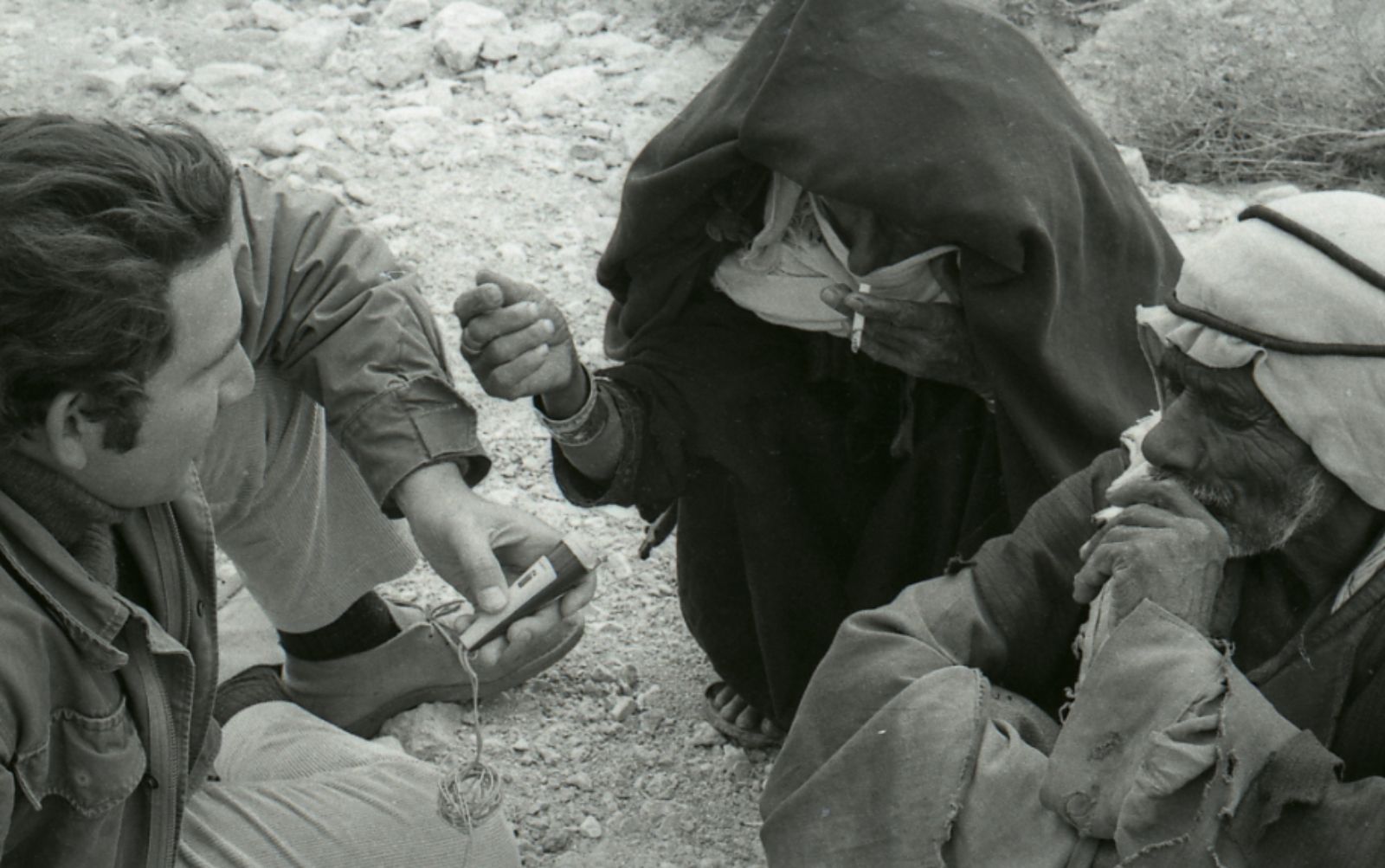

“I used to jog in the desert, and they were out with their flocks and herds and we spoke and they invited me to their tents, and I saw it was a very unusual and probably very old culture and I wanted to record as much of it as I could before it disappeared,” he explains.

“So I spent the next 50 years doing so.I bought a jeep and a tape recorder and went around. I met and stayed with hundreds and hundreds of people. In many groups I was even a member of the family, in a metaphorical way.”

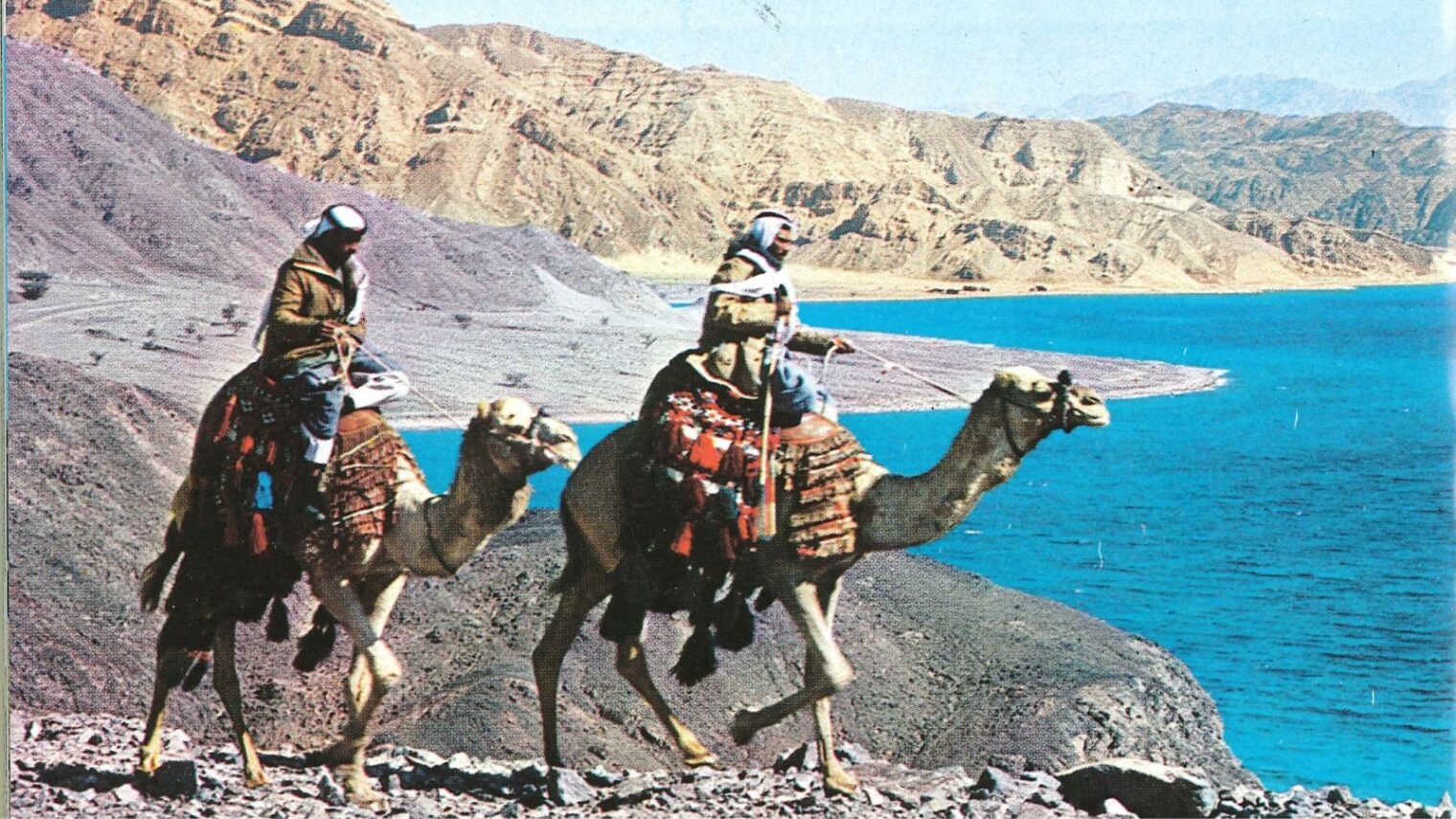

Bailey’s travels through the Sinai Peninsula (formerly in Israel’s possession) and across the Israeli desert led him to learn more about poetry, law, economics, proverbs and oral traditions and histories.

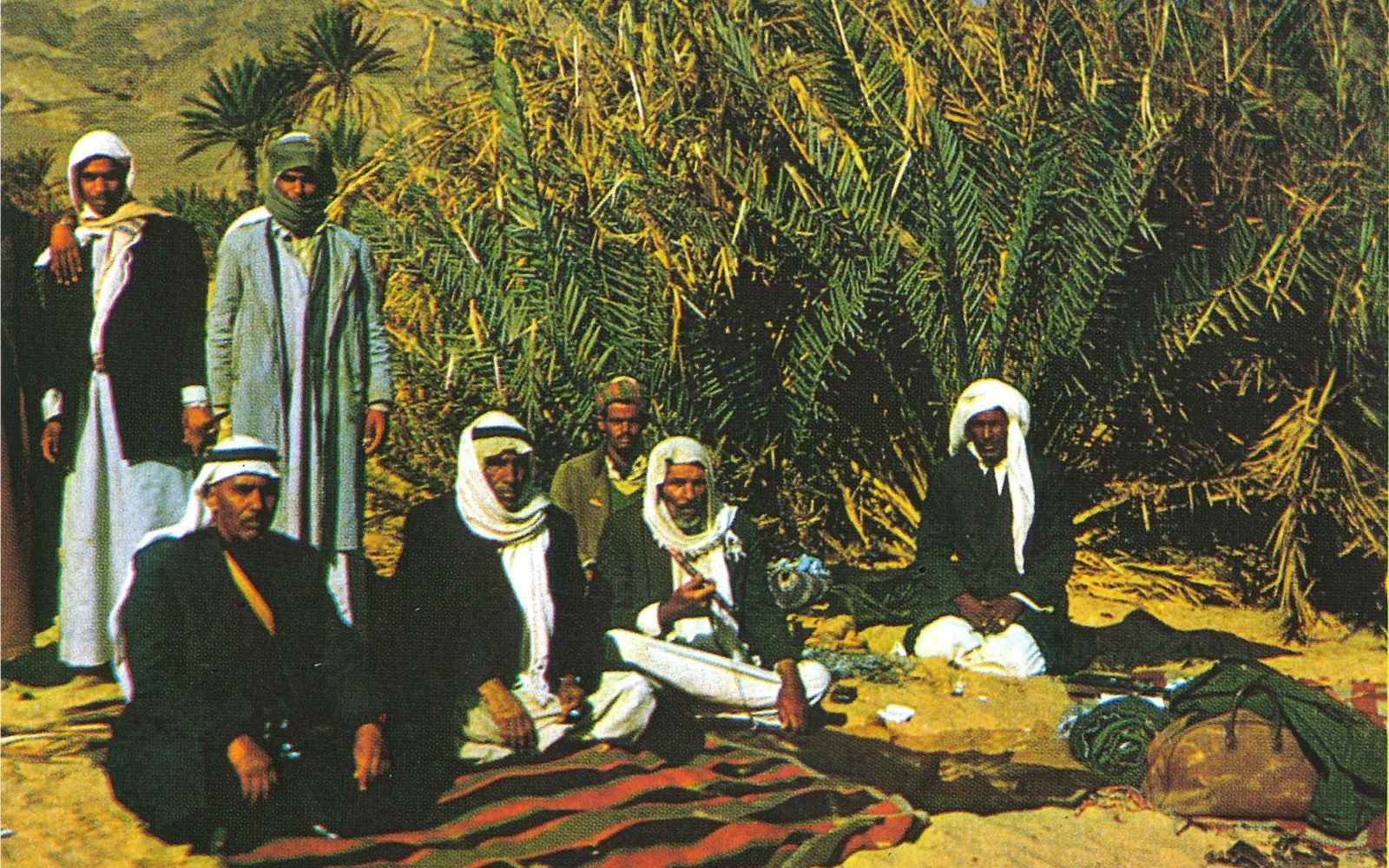

One family would introduce him to others and so on. “They always treated me with respect and friendliness. I don’t think there was an exception to it,” Bailey recounts.

“I spoke to them and I asked them questions and I observed what was going on around them. When there were subjects that I wanted to develop in detail, I recorded the conversations and the answers that they gave me. The subjects built up,” he adds.

He also became an advocate for Bedouin civil rights, for which he was awarded the Emil Grunzweig Human Rights Award by the Association for Civil Rights in Israel.

An ancient culture

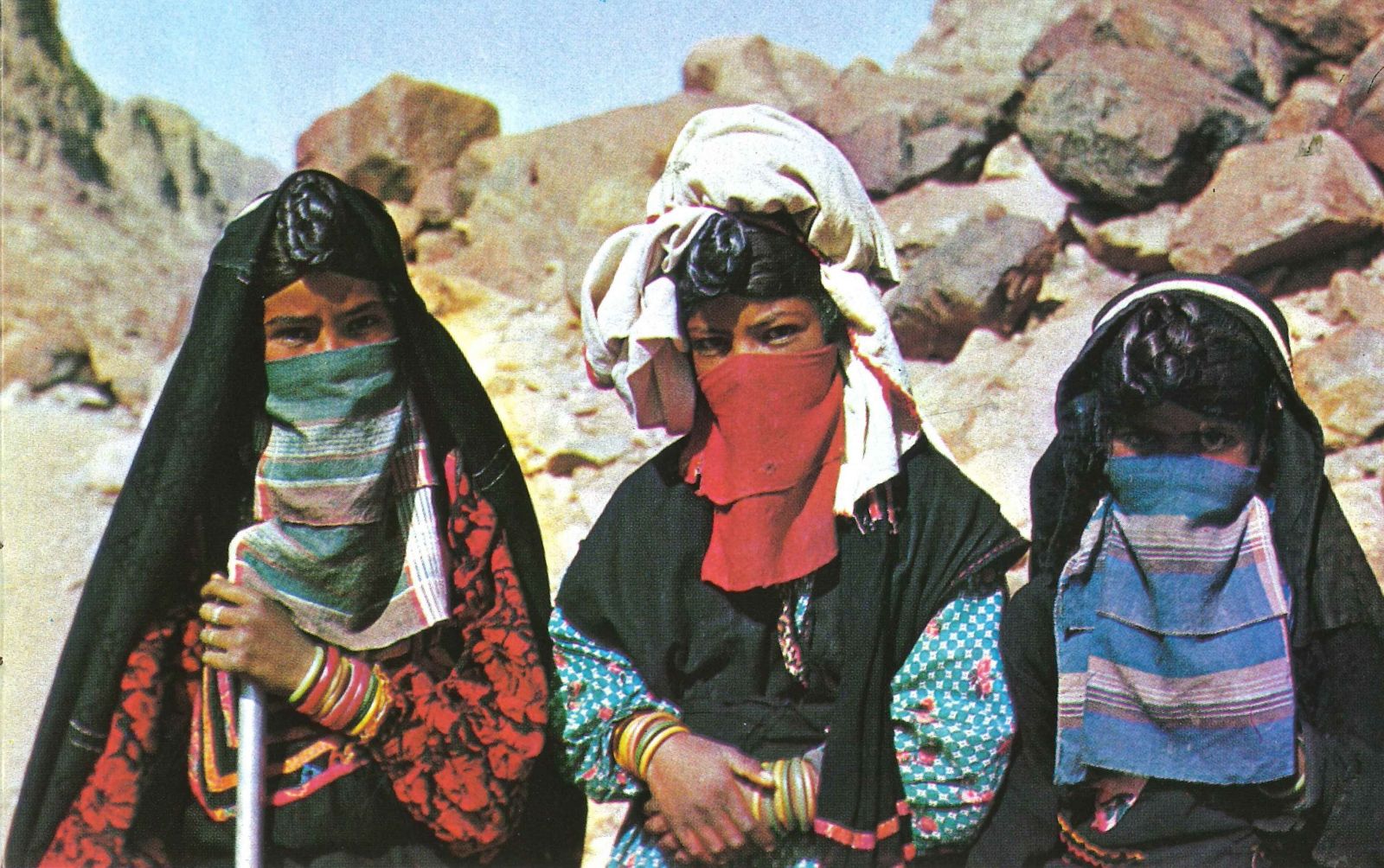

Bailey says the Bedouin appreciated that someone from the outside wanted to know about their culture, which may go back at least to 2,000 BCE.

What most interested him was that the Bedouin way of life managed to maintain itself in the desert over history.

“Just the fact that people like that could survive in the desert, in desert conditions, for such a long time, fascinated me. I found that since the desert doesn’t change if you don’t bring in water then survival in the desert doesn’t change either. You need the same systems and therefore the culture is very old,” he notes.

“Throughout history, there were never governments in the desert to protect people, so they had to protect themselves. They did that by organizing themselves into social groups because they could depend on these people. Each level of connection dealing with specific problems. They made their own laws which were logical for them and necessary for them.”

Traces of this social organization remain today.

“There are still clan connections and people do nominally belong to tribes even though the chiefs of the tribes have lost much of their power; people are more independent,” he notes. “Belonging to the tribe and clan are their main sources of security. It’s still a matter of importance for them.”

Is change good?

Bailey isn’t quick to judge whether the changes undergone by Bedouin society are positive.

There are welcome advancements in technology and education, especially in education for women. But the Bedouin community still suffers from discrimination and from a lack of services and resources.

“There are a lot of educated people now in the modern, Western sense. Women are now beginning to receive education and be in the outside world. There are hundreds of Bedouin girls studying at Ben-Gurion University and other institutions in the Negev,” he says.

“But it also has its downside. The fact is that they lost their freedom to roam in the desert and they lost traditional livelihoods that they were familiar with. Most of them come in on the lower rung of the socio-economic ladder.”

Yesterday’s host is today’s guest

Over his years of research, Bailey was surprised by the Bedouin community’s view on life.

“I was surprised by how they had a different attitude to life. Very different from ours. First of all, they were much more self-sufficient,” he notes.

“They were very non-materialistic. In other words, a person was not gauged in any way by their wealth; there were other criteria. They never considered themselves poor, even if by our standards they had next to nothing.”

Bailey says generosity became a central value in Bedouin life.

“Yesterday’s host is today’s guest. People moved around and there was no place for them to get shelter or repose or food or directions or anything except in tents that always had to be open to the outsider. That pleased me very much and interested me.”

Bailey, who undertook his research with a simple tape recorder, is gratified that his archive is being readied for the 21st century and made available to a larger audience.

“I think it’s wonderful because there’s a lot to learn about them,” he concludes. “It’s an exposure of their culture and way of thinking and we can see that they’re people like we are.”