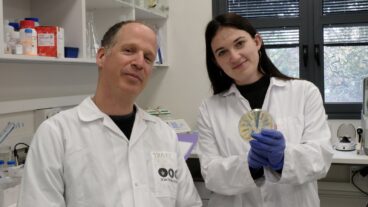

Key research toward identifying the HRD gene took place in the molecular and developmental genetics laboratory of BGU’s Faculty of Health sciences and the Soroka University Medical Center Israeli researchers are playing an important role in identifying a defective gene that causes a rare and usually fatal disease in Arab infants.

The study is the result of a unique arrangement in which an American scientist is coordinated the work of the Israelis at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, together with parallel research by Saudi Arabian and Kuwaiti scientists. This means that the Arabs were not actually “collaborating” directly with their Israeli colleagues, yet still allowed their findings to be pooled, which paved the way for the comprehensive understanding of the disease that led to the identification of the gene.

The findings of the study on the gene were published jointly in Nature Genetics a few

months ago, using research that was carried out without any contact between the Arabs and the Israelis. Dr. George Diaz of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City served as the coordinator, transmitting data to the various sets of researchers in order to eliminate the need for them to communicate directly.

The findings benefit Arabs alone: this gene affects, among others, the Palestinian and Bedouin populations in Israel, who were studied in the BGU research.

“Our first priority is to help and treat the Bedouins of the Negev,” Dr. Ruti Parvari told Israel 21c. Parvari is a member of the molecular and developmental genetics department of BGU’s Health Sciences Faculty and on staff Soroka Hospital in Beersheba. “At the same time, they are a unique population with certain genetic diseases not found in the general population. Information they can provide helps us identify genes and learn more about the biological processes they trigger.”

The recessive gene causing hypoparathyroidism retardation and dysmorphism (HRD) was found on chromosome No. 1 in 35 Arab families in the Negev, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait. In addition, a French physician reported on a case in a Moroccan family and another was found in a patient in Belgium. The findings indicate that a single Arab was the source of the gene mutation decades or perhaps centuries ago.

The discovery opens an opportunity for a deeper understanding of the cellular biology involved in the disease and makes prenatal diagnosis possible, Parvari told the Jerusalem Post, which reported on this story after the Nature Genetics article appeared.

The disease caused by the gene involves severe calcium deficiency that results in abnormally low birth weight, mental retardation, very slow physical growth, and a tendency to seizures. The disease has been compared to Tay-Sachs, a genetic disease found among Ashkenazi Jews.

A number of Israeli Bedouin families have taken advantage of prenatal diagnosis and have already aborted fetuses carrying the gene.

“We know that the Bedouins have a great religious difficulty with abortion,” said Parvari. “Our hope is that we can eventually find a way to prevent or treat the condition.”

All of the Arab couples studied by the BGU team were first or second cousins who married. Thus, increasing education to discourage inter-family unions is a possible directions towards preventing the genetic condition.

The research began when Soroka pediatricians Dr. Eli Hershkovitz and Prof. Rafael Gorodicher diagnosed children with HRD and found that it was a rare disorder passed on by parents who were non-symptomatic carriers of the gene. Every pregnancy of such couples has a 25 percent risk of an HRD baby. Parvari performed the molecular research on blood tests taken from the patients and their families.

At the same time, a team headed by Diaz in Manhattan published research describing a similar syndrome with the same chromosomal location as that found in affected Arab families in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Diaz, a human geneticist focusing on skeletal diseases, was eager to mediate the research. Knowing that scientists from the Arab countries were not permitted to be in contact with Israelis, even by e-mail, Diaz volunteered as coordinator of the project that found the exact location of the gene.

Putting all of the findings together was crucial, since the larger number of individuals who took part in the genetic study increased the accuracy of finding the exact section of the chromosome where the gene is located.