The study of the DNA of pathogens hidden in the bones of mummies could help avert or at least curtail a future plague – such as Ebola, Sars, West Nile Fever, tuberculosis or avian flu. Some microorganisms are very hardy and can live for thousands of years – in mummies, for example. Israeli researchers are among the world leaders in understanding how these ancient microbes provide clues about ways to control emerging and re-emerging diseases.

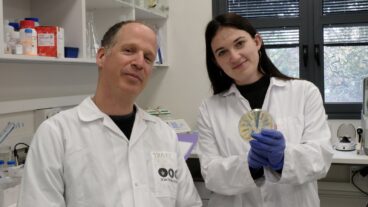

“Opportunistic microbes have evolved into today’s infectious diseases,” says Charles Greenblatt, Professor of Parasitology at Hadassah Medical School at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem – a leading voice in the new field of ‘Ancient DNA Analysis.’

Greenblatt and his colleague Mark Spigelman have lined up convincing evidence to show that the study of the DNA of pathogens hidden in the bones of mummies could help avert or at least curtail a future plague – such as Ebola, Sars, West Nile Fever, tuberculosis or avian flu.

The frightening speed and extent to which these diseases spread, has caught much of the health establishment unprepared, according to Greenblatt. From DNA analysis of old pathogens, they are now able pick up clues for intervention strategies.

The study of microbes in mummies can reveal a wealth of information about causative agents, disease prevalence in the past, evolution of pathogens, host genetic resistance factors, and networks of cross-infection – both plant and animal. Mummy microbe detectives search for a vector, or reservoir of infection – either human or animal. Stop the reservoir or block transmission from it, and you stop the spread of disease.

Greenblatt’s credo comes from a quote in his seminal book on the subject, Digging for Pathogens: ‘The most important experiments are the ones that nature has already done for us.’

Greenblatt and Spigelman also edited another book titled Ancient Emerging Pathogens and wrote a chapter in Medical Archaeology, which will be published by the American Society of Historical Archaeology this year.

Greenblatt’s own career is a convergence of different disciplines. He majored in Biology at Harvard where he graduated cum laude; completed an M.D. at the University of Pennsylvania; worked in different capacities with the National Institute of Health in the US, where he veered into parasitic diseases. Living in Israel since 1968, he has served as Chairman of the Department of Parasitology at Hadassah Medical School, Director of the Kuvin Centre for the Study of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, and Director of the School of Public Health and Community Medicine.

Greenblatt was lured into archaeology by Spigelman, the first to report on the isolation of tuberculosis (TB) DNA from ancient tissues. Intrigued by the chance to pull infectious disease secrets out of archaeological sites, they soon attracted a team of international scientists.

Indefatigable trackers of disease origins, Greenblatt and Spigelman used the latest molecular technology to analyze the DNA of TB and leprosy pathogens in a 2000 year-old burial tomb below the Cinematheque in Jerusalem.

“Even after the host dies, the pathogen lives. It is an adaptive genius, protected by a thick wall,” said Greenblatt.

Using DNA analysis of the pathogen found in bones from the Second Temple burial niche, the microbe sleuths found a family member infected with both leprosy and tuberculosis. (He was not buried in the same ritual manner as the others.) This was the first evidence of co-infection in ancient times. Studying the DNA in other ancient skeletons, they found that 25% had both diseases. These statistics compare with statistics on lepers today, 25% of whom die or are infected with TB.

“A victim of leprosy has a weakened immune system and is vulnerable to TB,” said Greenblatt.

In some cases, a healed TB lesion may have living bugs which are re-activated if the immune system fails. Spigelman discovered this when he analyzed DNA in TB victims in Hungary from 1780 to 1830. He found a 95-year-old mummy, (the star of a forthcoming National Geographic documentary), afflicted with a calcified lung lesion, a sign of a sleeping TB bug left from childhood. TB DNA was not found anywhere else in her body.

Studying records in the Hungarian town, Spigelman discovered that some families were free of the disease, suggesting natural resistance, or a resistance gene. An interesting note, Jewish immigrants to New York living in environmentally-stressed conditions, had the lowest infection rates in the city. Israeli Jews and Arabs both have low rates of infection.

“Over 4 million people die of tuberculosis each year. It is even a bigger scourge than AIDS,” said Greenblatt. TB is one of the oldest diseases in the world. Hebrew University researchers found it in the bones of a 17,000 year-old bison; others have found it in South America before European exploration.

“Air travel, crowded living conditions, antibiotic resistance have made the fight against infectious disease tougher than ever before,” said Dr. Irun Cohen, Professor of Immunology at the Weizmann Institute of Science, and Director of the Center for Emerging Diseases, a non-profit Israeli organization. Cohen has supported Ancient DNA study as an integral part of the Center’s work.

“When people were scattered all over the world, microbes were not so effective. They actually killed themselves. With the change in culture and people crowded together, they have become more virulent,” said Cohen. “The study of ancient DNA creates a new opportunity to see how microbes have modified themselves. It suggests clues as to how we can attack emerging diseases successfully. Vaccine programs and destroying all the infected chickens in Thailand, are examples.”

Fascinating stories aside, Ancient DNA experts can provide invaluable clues for disease intervention strategies: to trap a pathogen in a dead end; to block disease transmission by interrupting the parasite before it pounces on a victim; to target the switch that turns a microbe into a pathogen. Health experts are finally starting to listen.