Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the research showed the brain-activity patterns of people watching the same movie look very similar, regardless of their gender and age. Did you ever wonder if the thoughts that were going through your mind while you sat in a movie theater engrossed in a film were the same as your friend’s sitting next to you?

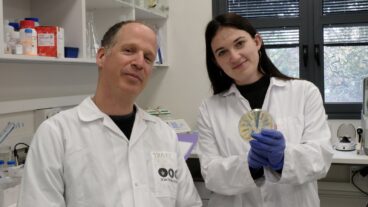

Neuroscientists and psychologists have long debated the question: to what extent are our brains alike? Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science have begun getting an answer to this question, Hollywood style.

They monitored volunteers while they watched Sergio Leone’s spaghetti western classic The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, starring Clint Eastwood – and they discovered that the different volunteers’ brains react in a remarkably similar fashion.

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the research showed the brain-activity patterns of people watching the same movie look very similar, regardless of their gender and age. Viewers tend to focus on the same faces and objects, even when they are looking at complex scenes.

“Despite the completely free viewing of dynamical, complex scenes, individual brains `tick together’ . . . when exposed to the same visual environment,” co-authors Professor Rafi Malach and Uris Hasson wrote in the journal Science.

“This similarity was so strong that you could take a small part of one subject’s brain and predict what will be the activity in the corresponding part of the brain of another person watching the same movie,” Malach told National Geographic.

Patterns of brain activity were most closely matched when the viewers were responding to surprising or emotionally charged moments in the film, such as gunshot or explosion scenes or sudden twists in the plot. Other brain areas that were in sync included the bits that light up in response to seeing faces or outdoor scenes.

The research also showed that different brain areas actually pick up different types of scenes, from a close-up of an actor to an outdoor scene, to delicate hand movements made by a character.

“Although we have a strong subjective feeling of unity when we watch a movie, this is actually built up of a sort of orchestrated jam session of activity in many brain areas,” said Malach. “Each becomes active depending on what is being shown on the screen.”

For the study, the researchers showed five people the same 30-minute segment of the film while they lay inside a large magnet. The technique, called functional magnetic resonance imaging, detects blood flow to different parts of the brain where information is being processed.

About a third of the brain activity of all participants was virtually identical, the study discovered. As a control test, they also scanned the volunteers as they lay quietly, and their brain patterns barely matched.

The point of the research, said Malach, was to find a way around a methodological handicap of the growing field of brain-activation research. Experiments in the field mostly involve static tasks meant to focus on one brain region at a time, but the brain does not usually work that way.

Giving subjects a more natural task let the researchers “find what a brain area ‘likes to see’ without the need to have any preconceived notion of its functionality,” he said.

According to Malach, the findings could help neuroscientists better map and understand our brains, and it may even help diagnose mental diseases in the future. He believes the research will help scientists map little-understood brain areas, and give scientists better insight into what kinds of images engage us and attract our attention and focus.

The movie experiment may offer a model for probing unknown brain-activity patterns in regions that are typically not reached by conventional experiments.

“This opens the way to rapid discovery of new specializations in the human brain, because it has the advantage of allowing us to study the brain without the need to assume ahead of time what each area is doing,” Malach said. “We also anticipate that it could be used as a rapid and sensitive diagnostic tool for mental cases, such as autism, Alzheimer’s, retardation, and perhaps even schizophrenia.”

One important application, he added, could be used to try to understand why children with autism do not engage with what they see happening around them.

“In regards to future studies, it turns out that this dynamic visual stimulation is a very powerful means for reliably activating the brain,” Malach told ISRAEL21c. “One of the assumptions – before doing the study – was that this kind of stimulation would be a bad choice for brain activation because everybody would react differently. What we found – due to the engaging power of the movie – was an effective and unifying way to activate the brain in a reliable and quick manner. It ‘s a potentially powerful tool for diagnostic purposes.”

Typical neuroimaging studies have generally been simple, abstract, and highly controlled. Volunteers may have been asked to move dots on a computer screen or respond to single-object pictures. The Israeli researchers, on the other hand, gave their subjects complete freedom in watching the movie. Volunteers were placed in an MRI machine. Equipped with earphones, they watched the film on a screen inside the MRI machine while their brains were scanned.

“It’s an interesting form of study for the patients, even children can be engaged. It’s an alternative to the usual laboriously, boring kind of paradigm,” said Malach. “We hope it’s a powerful way to develop a package of stimulating the brain to allow for the detection of disorders. We also had fun with it. It breaks the traditional conventions of doing everything in an exact and controlled situation.”

Malach says the researchers chose the 1966 Eastwood classic because it was a favorite of the lead author of the study, Uri Hasson.

“I really like this movie. It is a great one,” Hasson told the Sydney Morning Herald. Its unusual style of direction also made it particularly well-suited for the experiment, he said, because the camera repeatedly zooms in for facial close-ups and then zooms out for wider landscapes.

“We just let [the movie] run for half an hour,” Malach said. “The movie contains many object categories at the same time. It is dynamic, audiovisual, and has rapidly changing language and emotional aspects.”

People from different cultures also respond differently to movies, and this could be explored using the technique, Hasson said

Those with a DVD of the original MGM film can look at a compilation of scenes that the researchers found to evoke the strongest uniform response. Click here to download the neccessary software.