Imagine you’re walking in a busy place like Times Square in New York. There are tons of people around. As you make your way through the crowd, you notice several faces but ignore the rest. What makes your brain do that?

A new study published in the journal Nature Human Behavior describes how the unconscious mind processes human faces and the two types of faces it chooses to consciously see: those associated with dominance and threat and, to a lesser degree, with trustworthiness.

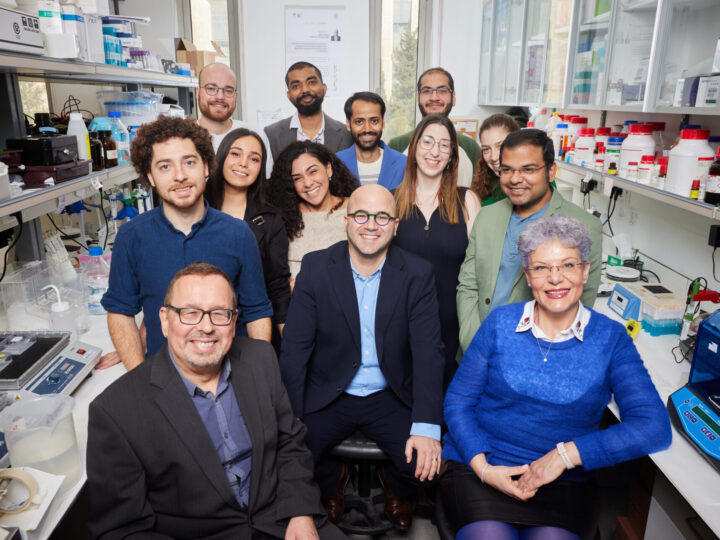

The study was conducted by Prof. Ran Hassin, a social psychologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Federmann Center for the Study of Rationality, along with Hebrew University graduate student Yaniv Abir; Prof. Alexander Todorov of Princeton University; and Prof. Ron Dotsch, formerly of Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

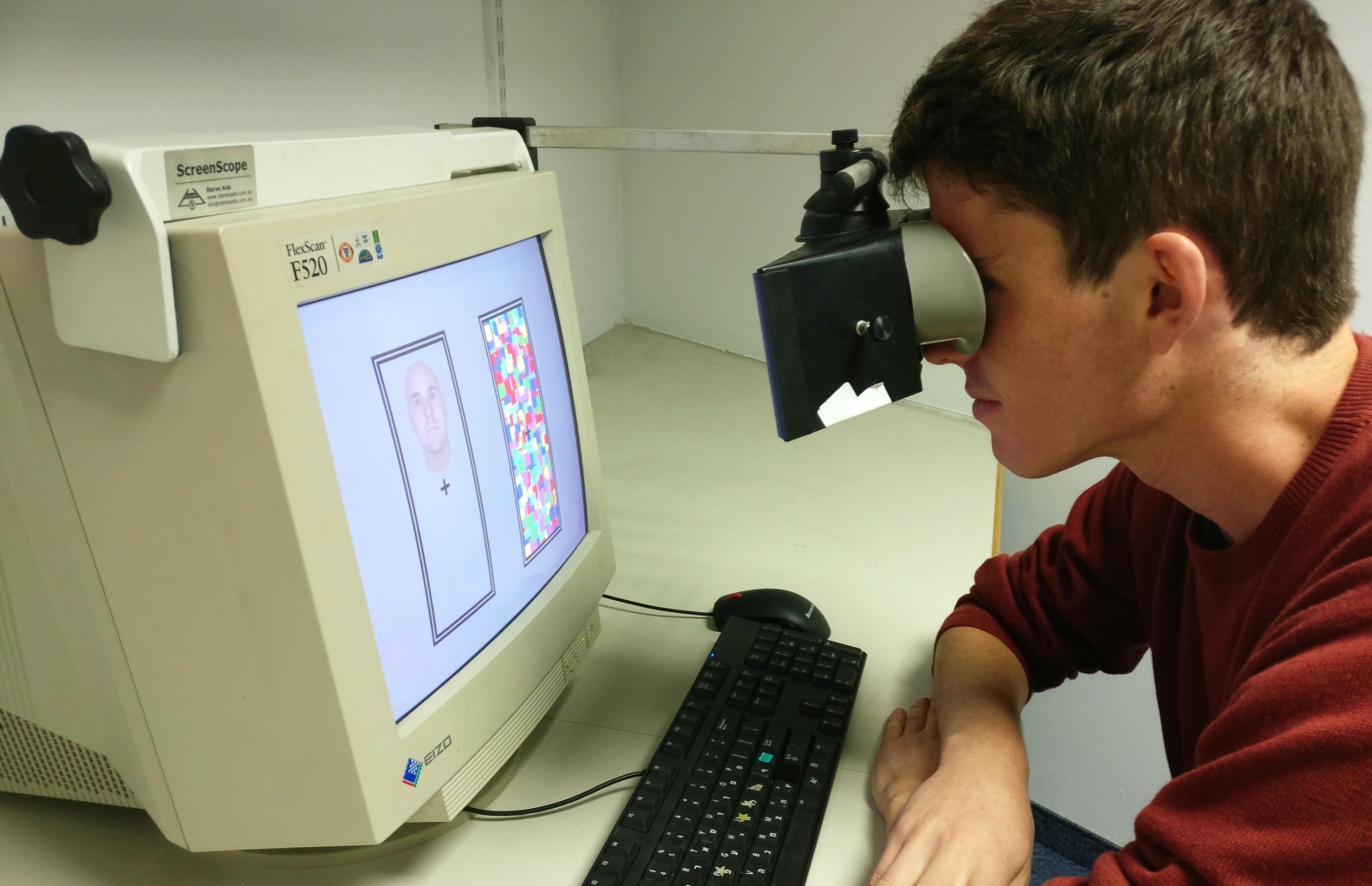

In a series of six experiments, Hassin and his research team showed 174 participants 300 sets of rapidly changing images. In one eye, participants were exposed to images of human faces, and in the other eye they were exposed to geometric shapes. They were asked to press a computer key as soon as they saw a human face.

It took the brain a few seconds to understand that it was seeing a face and then to “transfer” these images to the conscious brain for processing. The researchers observed that the facial dimensions most quickly registered by participants were ones that indicated power and dominance.

“Walking around the world our unconscious minds are faced with a tremendous task: decide which stimuli ‘deserve’ conscious noticing and which do not,” explained Hassin.

“The mental algorithm we discovered deeply prioritizes dominance and potential threat,” he noted. “We literally saw the speed with which these images broke through the unconscious mind and registered on a conscious-level with each key press.”

For the past decade, Hassin has focused his research on the human unconscious, specifically decision-making, memory, motivation and how opinions are formed.

“This study gives insight into the unconscious processes that shape our consciousness,” Hassin said. “These processes are dynamic and often based on personal motivation. Hypothetically, if you’re looking for a romantic partner, your brain will ‘see’ people differently than if you’re already in a relationship. Unconsciously, your brain will ‘prioritize’ faces of potential partners and deemphasize other faces.

“Likewise, the same might be true for other motivations, such as avoiding danger. Your eyes might pick out certain ‘menacing’ faces from a crowd and avoid them.”

Looking ahead, Hassin hopes these findings can pave the way toward a better understanding of autism, PTSD and other mental disorders.

“It might be possible to train and untrain people from perceiving certain facial dimensions as threatening. This could be helpful for those suffering from PTSD or depression. Likewise, we could train people with autism to be more sensitive to social cues.”

The study was supported by a grant from the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation.