New uses for the pomegranate could benefit Israeli growers who produce 3,000 tons of the fruit per year.Until recently, the medicinal powers of the pomegranate were best known to those who dabble in mythology or follow ancient Chinese medicine: In Greek myth, Persephone becomes betrothed to her kidnapper, Hades, king of the underworld, after eating the pomegranate seeds he offers her; and Chinese herbology offers pomegranate juice as a longevity drug.

But the pomegranate, whose tart and juicy seeds have always been enjoyed as a fruit, is now coming into its own as a modern medical resource. Two Israeli researchers, independently of each other, are developing a range of treatments and products derived from the fruit, which is cultivated throughout the Mediterranean; Israel grows 3,000 tons a year.

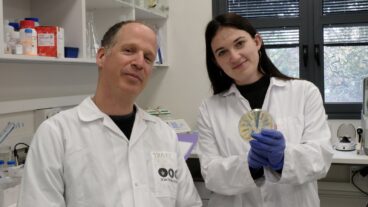

At the Lipid Research Laboratory of Haifa’s Rambam Medical Center of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Dr. Michael Aviram is using pomegranate juice to fight cholesterol and heart disease. And at Rimonest, a company funded by the Technion, Dr. Ephraim Lansky speaks of the fruit as a virtual cure-all – its juice, flesh, even its skin, he said, contain properties to counter not only cholesterol, but aging, and perhaps even cancer and AIDS as well.

Aviram, 53, a Technion biochemist, has spent the past 20 years trying to find ways to prevent and break down the deposits of cholesterol in the arteries – arteriosclerosis – that cause strokes and heart disease. Searching for natural antioxidants, he said he tested “twenty different things” before alighting on the pomegranate. Its juice, he found, contains a particularly powerful antioxidant, a flavonoid, which he said is more effective at fighting heart disease than those in tomatoes and red wine.

For the past year, he has been giving the juice to Rambam patients suffering from carotid artery stenosis – a blockage of those arteries that bring blood to the brain – and he said the results have been rapid and impressive. “I’ve been seeing improvements after the first month,” he said.

In fact, Aviram said, many high-risk patients who would otherwise have needed bypass surgery have been spared that simply by drinking pomegranate juice. The only problem he’s had is that some find its taste overpoweringly tart. So he’s now working on isolating the flavonoids in pill form.

Aviram details his research with the assurance born of years of experience, in a hospital office that exudes calm professionalism. Graphs and charts line the walls, interrupted only by his dozen or so diplomas and certificates.

The offices of Rimonest, just a 20-minute drive away, make for an acute contrast. Here, all four office walls feature a shelf packed with unmarked gleaming red bottles of homemade pomegranate wine, the remnant of a 1997 experiment. There’s a wine press in a distant corner. A storeroom looks like a cross between an organic pantry and a lab. A side table features a handful of forlorn dried pomegranates. On other shelves and tables, books on homeopathic medicine mingle with conventional medical texts. From the organized chaos, his curly hair only partly contained by his kippah, Ephraim Lansky emerges.

The primary shareholder and head researcher of Rimonest, Lansky, 48, is a University of Pennsylvania-trained doctor, with a PhD in psychology and biology and qualifications as a homeopathic physician and acupuncturist as well. He said he is interested not only in the juice of the pomegranate, but in the whole fruit. He’s already marketing Cardiogranate, a juice concentrate which he said fights high cholesterol, and is now moving on to a cosmetic line – anti-aging creams, massage oils, masques and toners – using estrogen-rich extractions from pomegranate seeds and peel, which he hopes to unveil this year. A practitioner of homeopathic medicine, he also prescribes pomegranate juice for fever, and gives it to menopausal women for hot flashes. And although the 1997 wine failed, he sold a thousand bottles of an improved version, kosher for Passover, at Israeli health food stores last year.

But over cups of green tea, fresh leaves floating in the glasses, he takes pains to stress that these are mere diversions from his work on what he believes to be the pomegranate’s more serious pharmaceutical possibilities, in areas such as breast and prostate cancer, leukemia, even AIDS. “I see this as as a pharmaceutical company,” he said. “The idea is to finance the pharmaceutical development by selling the wines, creams and so on.”

Established in February 1999, Rimonest has only a handful of regular employees handling research and some of its marketing. So while Lansky and his colleagues produce the pomegranate extracts themselves, they farm out all the pharmaceutical applications and testing to other, larger labs, in Israel and overseas. “Our biggest research cost is UPS,” he jokes.

By his telling, the results are remarkable – although he stresses that some of the research is still in its early stages.

Applying pomegranate wine and seed oil to human breast-cancer cells in petri dishes, he said he has been able to stop the cells reproducing, prevent the disease spreading and stimulate apoptosis – the process whereby the body destroys the cells. Stage two of this research, with tests on mice, is about to begin, with labs in Tel Aviv’s Beilinson Hospital and the Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

Lansky also cites research overseas which, he said, suggests that pomegranate extracts can be used to counter viruses, such as HIV and herpes.

Speaking of the pharmaceutical industry in general, Lansky suggests that “economic pressures” can lead major companies to suppress treatment breakthroughs. “Did you ever see the movie ‘The Man in the White Suit’?” he asked, referring to a 1951 British comedy starring Alec Guinness. “This man invents a white suit that doesn’t stain or rip, and the textile industry tries to kill him.”

While Lansky clearly regards his favorite fruit as a cure-all, Aviram is considerably more circumspect. “I don’t believe that one fruit can do everything,” he said firmly. “There is no miracle fruit.” Asked about Lansky’s research and claims, Aviram said that the real test comes not in petri dishes or with mice, but in patient trials. “It’s very difficult to say that this or that will work on cancer just because you saw something in a test tube or in cells.”

But Lansky is resolutely confident and, for graphic support, invokes the Doctrine of Signatures, “the ancient idea that the Creator left a signature on the plants to tell you what they’re for.” At this point he holds up a pomegranate in one hand and, with the other, opens a medical book to an anatomical diagram of the female breast.