Celebrating the Gregorian calendar new year has always been a topic of controversy in the Jewish state. The Jewish calendar, after all, predates Pope Gregory XIII’s calculation by some four millennia, and the region functioned for centuries under the Ottoman Empire’s rumi calendar.

Nonetheless, the Gregorian calendar was adopted for civil use with the British conquest of the Ottoman Empire, on March 1, 1917, and the beginning of the year reset to January 1 in 1918.

In the first decade of the British Mandate, the local Orthodox Christian population marked the new year according to the Julian calendar in mid-January, Muslims celebrated the new year in summer, and the Jewish population honored Rosh Hashana in early fall.

British Army soldiers stationed in the region had their big blow-outs at Christmas (see “Biscuits, bully beef and beer”), but by the mid-1920s, with British officialdom firmly in place, New Year’s Eve celebrations were organized. In 1927, several wives of British bureaucrats based in Jerusalem are recorded as having held a dinner party followed by a ball on New Year’s Eve.

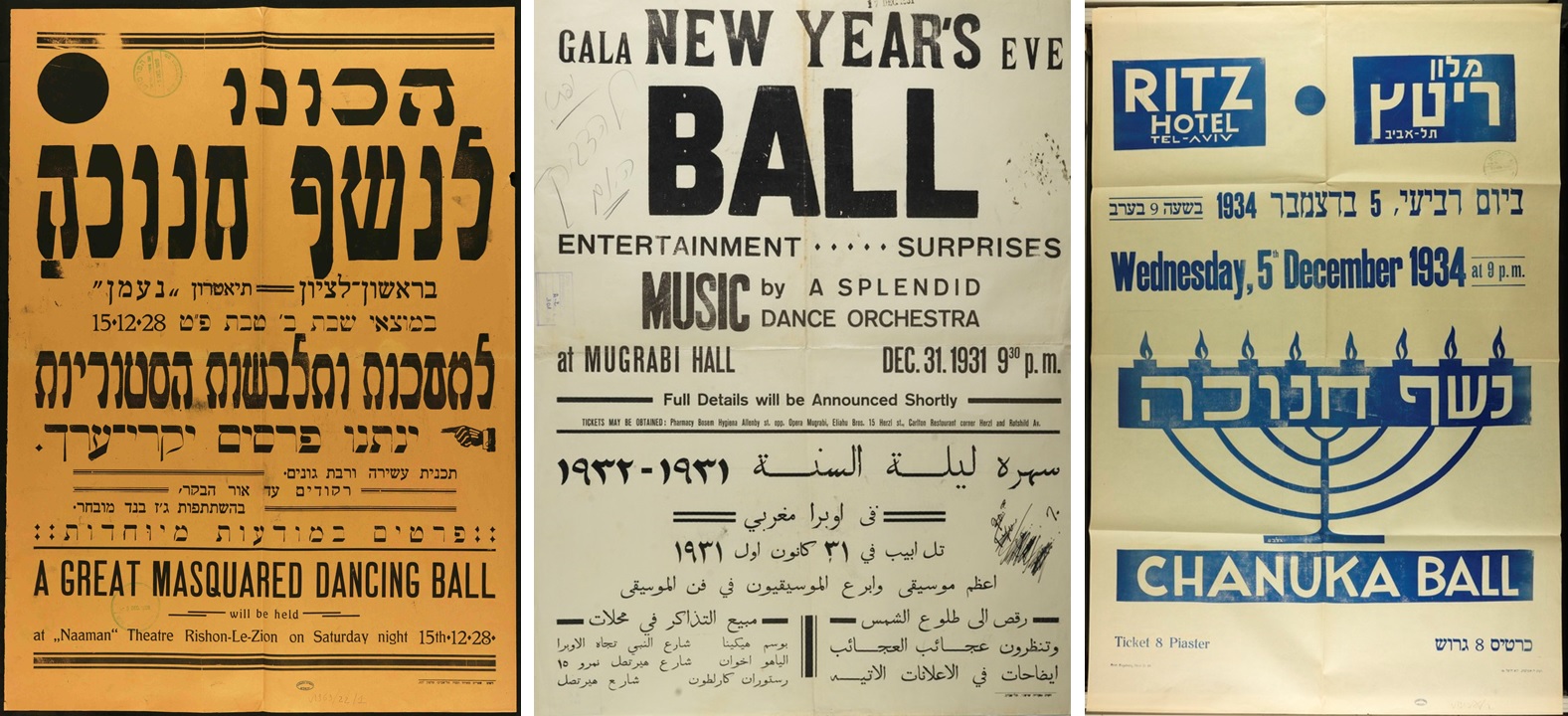

The Jewish population of pre-state Israel in the 1930s didn’t celebrate the Gregorian New Year, and instead embraced Hanukkah as its winter celebration.

Advertisements for New Year’s Eve celebrations, even if they were held at the Jewish-owned Mugrabi Theater in Tel Aviv, were targeted to English and Arabic speakers. The Jewish population announced its mid-December Hanukkah balls in Hebrew.

In the early 1930s, Jewish immigrants from Austria and Germany, fleeing the rise of Nazism, brought with them a more cosmopolitan lifestyle. This included a formal way of dressing and speaking, punctuality, summer afternoon tea dances, and winter Silvestertag parties.

The 1932 New Year’s Eve “special dance” at Haifa’s Café Vienna promised dancing from 9pm till 3 in the morning, as well as “Attractions, decorations, serpentines (belly dancers) and confetti (sweets).”

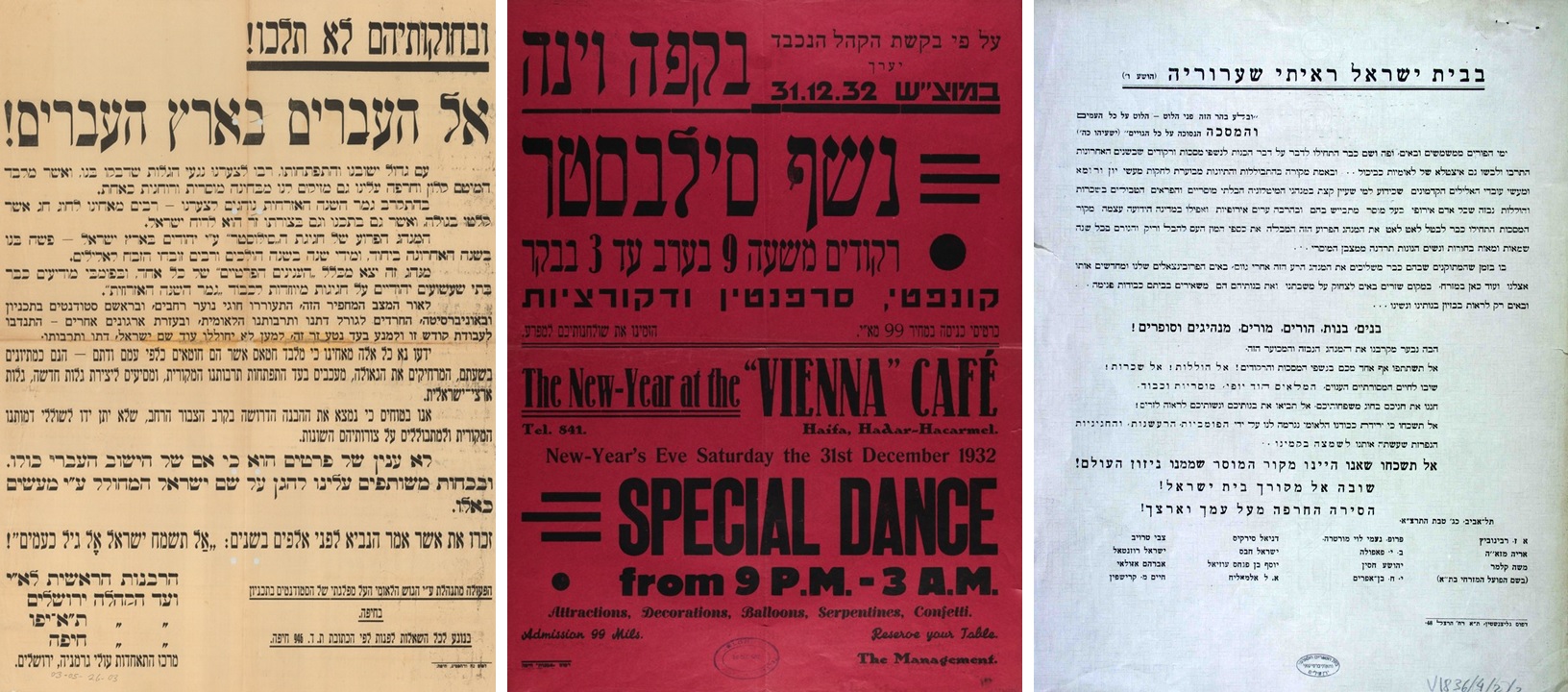

There was backlash from the Orthodox Jewish establishment and from the Jewish intelligentsia, who felt that these parties were not in keeping with good Zionist values. Jews also shied away from the German name for New Year’s Eve, “Silvester,” as “Saint Sylvester’s Day” honored third century Pope Sylvester I, considered by Jews to have been an anti-Semite.

Resolution to ban New Year’s Eve parties

In 1931, a group comprised mainly of representatives of Mizrachi Workers Party warned against masquerade balls. In 1934, newspaper Doar HaYom reported that the Tel Aviv City Council passed a resolution to ban New Year’s Eve celebrations in Tel Aviv.

“In the second half of the meeting, conducted by deputy mayor Mr. Rokach, two questions were put forth for discussion: A) the question of the Silvester holiday pervading Tel Aviv and B) the treatment of the Hebrew language by the new immigration, primarily, the German immigrants. A long argument arose about these two questions, in particular the second… Regarding the first question, Mr. Rokach’s proposal was accepted, stating that the Tel Aviv municipal council views this foreign custom of Silvester parties as absolutely undesirable, contrary to the spirit and traditions of the people of Israel, and requesting that all coffee houses and large event hall owners in the city not organize Silvester parties. A committee was selected to broach the matter with cafe owners, etc.”

Perhaps in response, the Central Union of German Olim in Jerusalem supported a statement issued by the Chief Rabbinate and the municipal committees of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Haifa, that read, in part: “As the end of the civilian year draws to a close, to our regret, many of our brothers engage in celebrating a holiday of the Diaspora that is, both in content and in form, foreign to the spirit of Israel. The wild custom of ‘Silvester’ celebrations organized by Jews in the Land of Israel has invaded us, particularly in the last year, and from year to year more engage in idolatry.

“This tradition is no longer an individual ‘private affair’ as Jewish-owned houses of entertainment are publicly advertising special celebrations honoring ‘the end of the civilian year’… and by joining forces we must protect the name of Israel, which is being tainted by such deeds.”

Students from the Technion and Hebrew University, it stated, were mobilized to keep other young folks away from the New Year’s Eve revelries that were apparently spilling out into the streets.

But you can’t keep a good excuse for a party down. Despite the attempted bans – and it is unclear if these were ever enforced – and throughout the decades, secular Israelis, particularly those in media and the arts, have partied on New Year’s Eve.

Fir trees and presents

On a more serious note, each year on the upcoming New Year,Israel’s president hosts the heads of the Christian communities in Israel.

In the 1990s, immigrants from the former USSR brought a new tradition to Israel, the Soviet holiday of Novy God (Russian for “New Year”).

Conceived by the Communist regime as a non-religious New Year’s holiday, Novy God nonetheless borrows from traditional Christmas symbols: a bearded elderly gentleman named Ded Moroz and his companion snow maiden Snegurochka, fir trees decorated with tinsel and lights, gifts under the tree, and family dinners.

Most Israelis don’t have any connection to Novy God, as it is celebrated mainly in communities with large first- and second-generation Russian populations. But in 2018, at least one politician decided to make a play for the Russian vote with a toast to Novy God.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)