It was a ritual for anyone traveling to Israel in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s — even on through the ’80s. No sooner had one’s feet touched the tarmac of what was then called Lod Airport, then those very same feet trotted straight to 185 Dizengoff Street to buy Nimrod sandals.

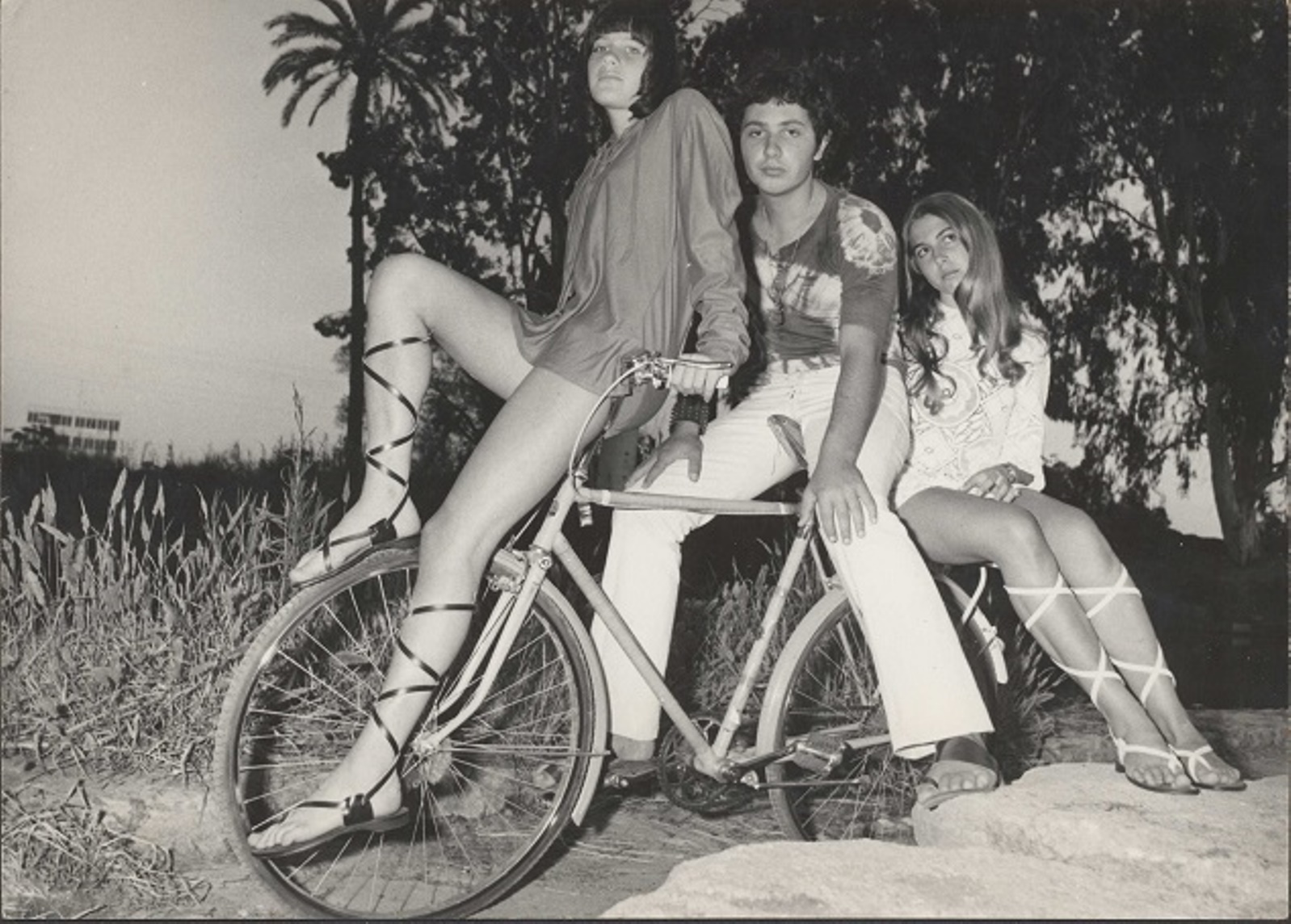

And once those sandals were on, they stayed on for the duration of the summer, a sign that one was well and truly becoming Israeli.

The conflation of Israeliness and sandals – specifically the style known as Bible sandal made by the Nimrod company — is the subject of a new exhibit at the Eretz Israel Museum Tel-Aviv.

“The Sandal – Anthropology of a Local Style” is an exhibit that “seeks to celebrate an object that has become identified with a place, look at the artisans who make them and the people who wear them, and learn how two horizontal strips of leather became a clear and distinct form that has circulated among manufacturers for over ninety years. This, despite the constant change of technologies, consumers, and tastes.”

Curator Tamar El Or, professor of anthropology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, has done extensive research on the topic as author of the book (in Hebrew) Sandals – An Ethnography of Israeli Style. Her paper (in English), published in American Anthropologist entitled, “The Soul of the Biblical Sandal: On Anthropology and Style,” focuses on Nimrod and serves as the basis for the current exhibition.

El Or writes, “Zvi Rosenbluth was a shoemaker in Eastern Poland (Galicia) at the beginning of the 20th century. His son Kalman fled Poland during World War I and found shelter (but not citizenship) in Holland near The Hague, where he married Feige and had four sons and two daughters. Kalman worked repairing shoes. In 1933 he immigrated to Palestine with his family and in 1935 settled in Tel Aviv, where he continued his shoe repair business.

“In 1937 the family rented a two-story building on Dizengoff Street and lived above the workshop. For a while, Kalman Rosenbluth and his sons tried to produce shoes as well as repair them. When the oldest brother Josef took over the business, he changed his last name from Rosenbluth to Ben Artzi (son of my land) and soon became known as just Artzi (my land). In 1944, with one brother serving in the British Army’s Jewish Brigade and the other training with the local militias, Artzi registered a shoe company, Nimrod Ltd.”

In 1960 and 1961, El Or notes, Israelis were captivated by the archaeological discoveries in what came to be known as the Cave of Letters, near the Dead Sea. Archeologist Yigael Yadin discovered a leather pouch containing documents dating from 96 to 134 CE, which had belonged to an upper-middle-class Jewish woman named Babatha (also Bavta). In addition to the cache – comprising legal contracts concerning marriage, property transfers and guardianship – were personal effects that included a pair of leather sandals.

The footwear – two millennia old but with a modern look — inspired Tel Aviv shoemaker Artzi (Josef Rosenbluth) to fashion a new model he called “Bavta” and feature it on the cover of the Nimrod summer 1965 catalogue.

El Or writes, “The promotional story ended with these words: ‘In any case, one must admit the resemblance between this ancient sandal and those worn by the style-conscious young Israeli sabra.’”

Rosenbluth didn’t invent the classic “biblical” sandal. That model – two buckled horizontal straps made of brown or black leather – was already worn widely by kibbutz members from the 1930s on.

However, adulation of the proletariat among city-dwellers transformed the simple sandal into part of a national identity, maintains El Or. “The sandal, then, became an object of the admired… The esthetic of the two brown straps stood for the ethics of the worthy locals.”

Indeed Srulik, the beloved Israeli sabra created by cartoonist Dosh to symbolize the brash young country, was never without his shorts, kova tembel and, of course, sandals.

However, El Or believes that the sandal’s deep association with “Israeliness” was Rosenbluth’s brainchild. “Artzi connected the sandal to the past, or to a number of specific pasts. The texts he wrote for the catalogues speak of the Land of Israel as the land of the sandal. He drew a direct line from Bavta of the Judean Desert across 2,000 years to the feet of his urban customers.”

“Between the early 1960s and mid-1970s, Nimrod was synonymous with Israeli sandals, which were synonymous with biblical sandals, which were an Israeli thing.”

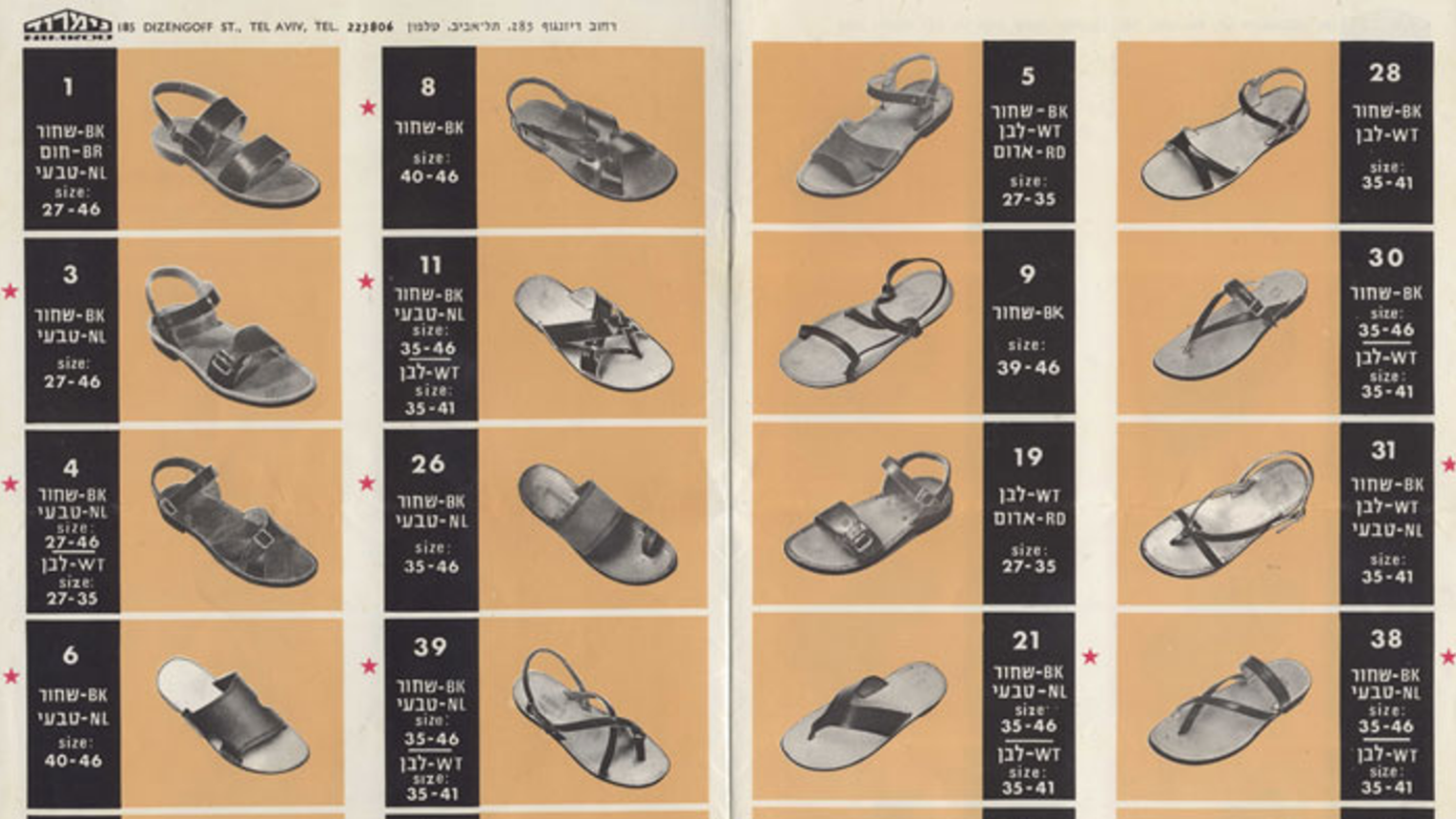

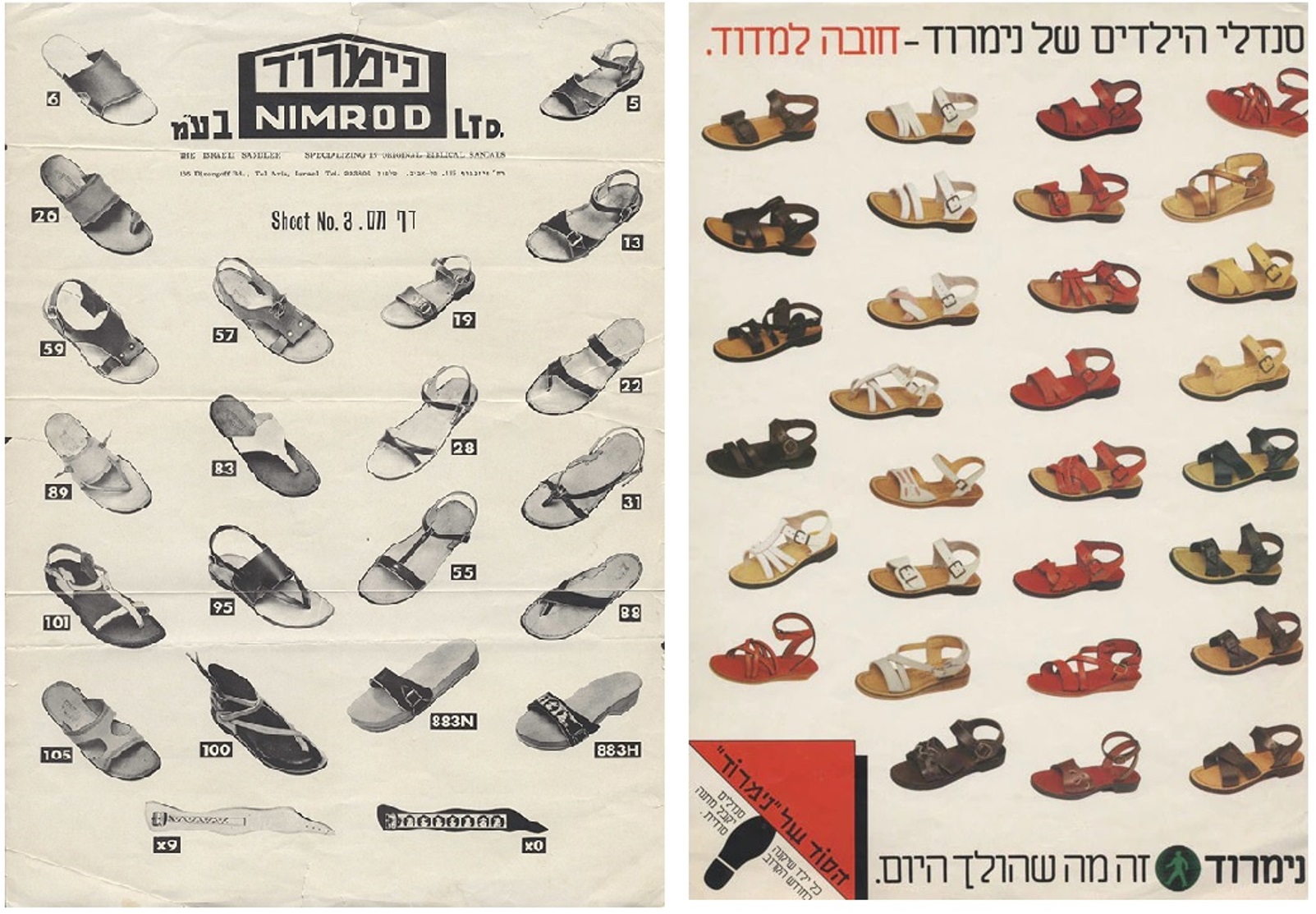

Nimrod sold its wares exclusively at its shop on Dizengoff and also through catalog sales. The latter was an unusual marketing tool for an Israeli company at that time but, El Or points out, Artzi was a canny businessman who knew foreign tourists made up a good part of his clientele.

Over the years, Nimrod created other styles influenced by other cultures and histories: ancient Rome, ancient Egypt, India, Mexico and more. Their sandals were not cheap but one pair lasted forever. Up until the late 1970s, there were few companies that could compete with Nimrod in terms of quality. When the Likud party came to power in 1977, the Israeli market gradually opened to foreign exports, and Nimrod’s popularity waned.

El Or: “The most reliable of Nimrod’s customers, the youngsters, wanted sneakers. Gali, another family-owned company, created designs like the old Nimrods but with newer technologies, and produced local versions of the U.S. sneaker. Now, both the masses and the upper-middle class had alternatives.”

“Health sandals” were another alternative with imported brands like Birkenstock and Teva, and local manufacturer Teva-Naot gained both popularity and market share.

After a decade of flagging sales, in the 1990s, Nimrod signed a contract with German children’s shoe brand Elefanten and opened the first of a chain of stores, which today are found all over Israel. Nimrod also represents the British brand Clarks in Israel.

In 2016, riding a wave of renewed interest in Israeliana, Nimrod launched a capsule collection of 1960s-inspired models, produced at its factory in Beersheva. The reproductions were almost exact, aside from one technological change for the better: sweat-absorbing padding in the soles. The “retro” designs are available via the Nimrod website.

Today, Israelis wear both locally manufactured and imported sandals but, as El Or points out, the iconic shape remains. “The value may change, the manufacturers may change, but there is something in the form that stays, and Israelis, or certain Israelis (including Arabs and Bedouins), will look for that form—two horizontal straps and much exposure of the foot.”

As for the original Babatha’s sandal — as it’s come to be known – it is on display at the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.