Last December, an Israeli boy was hiking with his family near Tel Beit Shemesh when he spotted the head of an Iron Age fertility goddess figurine. The Israel Antiquities Authority expressed its gratitude to eight-year-old Itai Halperin with a certificate of good citizenship and an invitation to him and his classmates to tour the IAA archive and participate in a real dig.

In January, seven-year-old Ori Greenhut stumbled across a 3,400-year-old statuette while scampering up an archaeological mound at Tel Rehov. He, too, got a certificate and a class presentation from IAA regional archeologists.

Accidental finds are not at all rare in Israel, where archeological treasures lurk in abundance underground and underwater.

“Israel is a very small country, intensively settled over thousands of years, and there are 37,000 registered archeological sites, so almost everywhere you have the potential to find things,” says Yardenna Alexandre, an IAA research and field archaeologist stationed in the Jezreel Valley.

But it seems the random discoveries have been coming fast and thick lately.

In February, six friends on a recreational dive in the Mediterranean coast off Caesarea chanced upon a trove of nearly 2,000 gold coins from the 10th century Fatimid Caliphate. The IAA stated that it is the largest cache of old coins ever discovered, and praised the divers for having “a heart of gold that loves the country and its history.”

The following month, kibbutznik Laurie Rimon was hiking in the North when she happened upon an extremely rare gold coin minted by Roman Emperor Trajan in 107 CE.

“There does seem to be a concentration of finding things over the past year,” Alexandre tells ISRAEL21c. “There may be several reasons aside from coincidence.”

She explains that when former politician Yisrael Hasson became chairman of the IAA in December 2014, he placed a priority on community involvement and educational programs to engage the public, especially schools, in archeological activities such as dig-for-a-day events.

“Antiquities and archeology is much more prominent in the media today, and that brings awareness,” says Alexandre.

“Hiking is very popular in Israel, and people may have been finding things and keeping them, whereas now they see that we encourage them to follow the law of turning them in.”

By law, antiquities belong to the state and may not be hoarded, sold or traded.

The certificate of good citizenship, the tours and media attention all are well-deserved incentives to do the right thing, she adds. “As a government organization, we haven’t got funds for giving rewards, but we want to educate people and make them feel this is part of their heritage whether they are Jewish, Christian or Muslim.”

Doing the right thing

Rimon, finder of the rare coin of Trajan, tells ISRAEL21c that friends from the United States saw her story covered on TV news and talk shows. In addition to Israel, she granted interviews to reporters from Irish National Radio, the Canadian Broadcasting Company and the BBC and Huffington Post.

“A lot of people said I did the right thing by turning it in, while others said, ‘Why didn’t you just pocket it?’ I’m not the sort of person who would have sold something like this, but I’m sure there are tons of stuff people find and don’t turn in,” says Rimon, a native of Connecticut who moved to Kibbutz Kfar Blum in 1973.

She does wish she’d had time to show the coin to her family before giving it up. But everything happened very quickly, she relates.

“I have hiked with a group called Mike’s Hikes in the eastern Galilee every Wednesday for the past 11 years,” she tells ISRAEL21c. “On March 2, during our usual hike, I sat down for a break among the ruins and when I got up I saw something shiny. At first I thought it was 10 agorot,” Israel’s smallest denomination.

“When I showed it to a few of the others, they said, ‘Laurie, it’s gold, it’s ancient, it’s real, you’re a millionaire!’ We caught up with our guide, Irit Zuk-Kovacsi, who took a picture and mailed it to a tour guide who knows old coins. He texted her back that it’s real and it’s rare. He approached the IAA and sent back more details. But it didn’t sink in what a treasure it was.”

Rimon’s phone soon started ringing. Not realizing it was the IAA, she ignored several calls and text messages. “So they called Irit and she told them where we were.”

Nir Distelfeld, an inspector with the IAA Unit for the Prevention of Antiquities Robbery, met up with the hikers near the Jordan River. “I pulled the coin out of my pouch to show him, and I said, ‘I guess I have to give it to you, don’t I?’ They’d already ordered photographers for 9 o’clock the next morning,” says Rimon.

‘Almost everywhere you have the potential to find things,’ says IAA research and field archaeologist Yardenna Alexandre.

The following day, Rimon and Distelfeld, other IAA experts and a camera crew spent three hours at the site. Her experience was documented on film and the area was scoured, unsuccessfully, for further finds.

“Perhaps someone stole it from somewhere else and dropped it there,” Rimon speculates. “It was so shiny it looked like it was minted yesterday.”

https://youtu.be/7Gl3dArsfF4

Call the IAA

Distelfeld praised Rimon for handing over the “extraordinarily remarkable” coin. Her hiking group was rewarded with a tour of the coin collection of the IAA in Jerusalem, which is not open to the public.

“It is important to know that when you find an archaeological artifact it is advisable to call IAA representatives to the location in the field,” he added. “That way we can also gather the relevant archaeological and contextual information from the site.”

The IAA website lists phone numbers for the north, south, central and Jerusalem regions.

Items turned over to the IAA go into its storerooms and become available to researchers.

“For example, the figurine found by a boy in Tel Rehov was given to Prof. Amihai Mazar, who excavated at the site, and he will include it in his published report,” says Alexandre. “It’s more complete than other figurines he’s found in years of excavation.”

Alexandre notes that it is illegal to look actively for archeological finds without a license.

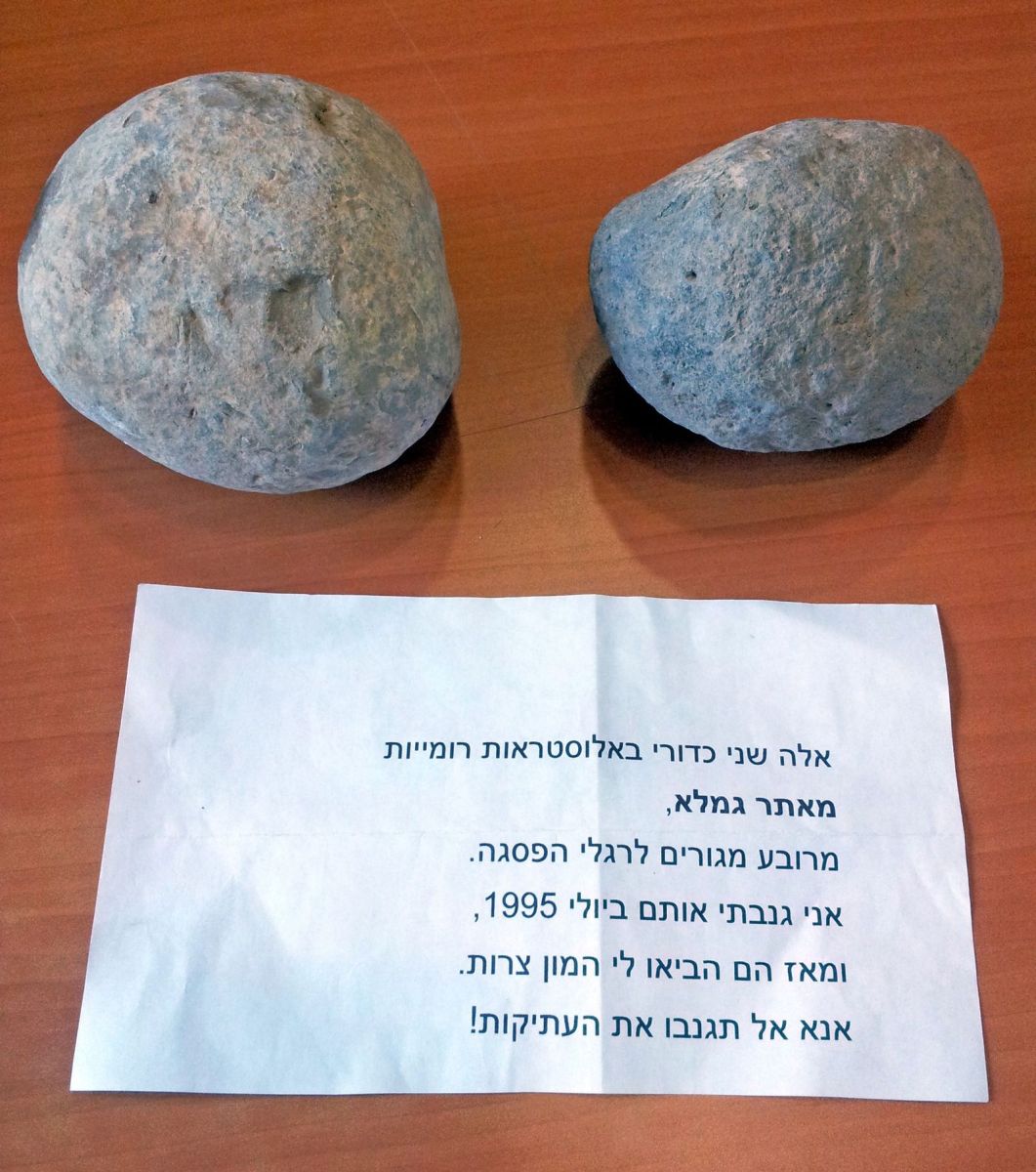

Last July, an anonymous person left a bag at the Museum of Islamic and Near Eastern Cultures in Beersheva, containing two valuable relics he had found 20 years earlier.

The accompanying note said, “These are two Roman ballista balls from Gamla, from a residential quarter at the foot of the summit. I stole them in July 1995 and since then they have brought me nothing but trouble. Please, do not steal antiquities!”

“He had a conscience that he was doing something wrong,” comments Alexandre.