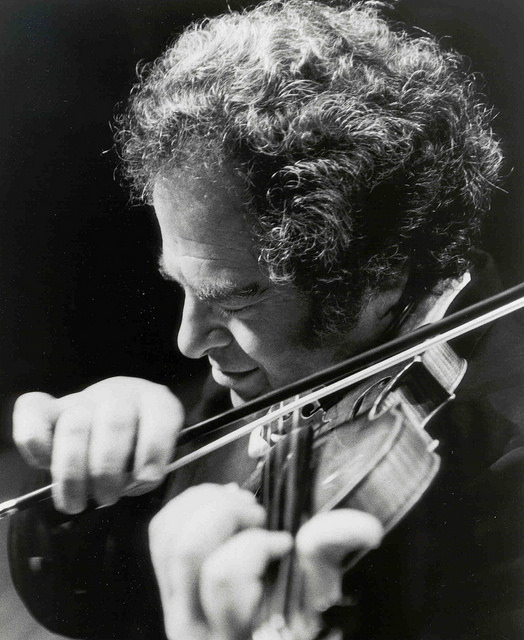

Shortly before a special rehearsal that was open to the public, several young musicians talked with reporters about what it’s like to be taught, mentored and conducted by their maestro, world-famous violinist Itzhak Perlman, who spent his childhood in Tel Aviv.

In Israel for two-and-a-half weeks in April as part of the Perlman Music Program (PMP), the 13- to 19-year-old string players sit in a row next to Perlman and his wife, Toby – herself trained as a classical violinist – to discuss their experiences.

“He has helped me find what I want to say in music and to put my heart into it. He has always said that there are many, many ways to play a piece,” says one participant.

Some are native Israelis; others have arrived at the Tel Aviv Conservatory from Australia, Canada, Hungary, Norway and the United States. All 37 were hand-picked by Perlman for their exceptional talent.

“For me, to be with the program in the country of my birth – and even in this neighborhood, not far from where I grew up – is quite special,” Perlman tells ISRAEL21c.

“And it gives me the opportunity to see if I can teach in Hebrew,” he quips.

Given the course of his history, teaching in his first language would seem to be a small challenge for the 69-year-old legend who began playing the violin when he was four. The same year, he fell ill with polio and nearly died. After a year of convalescing, his legs were left paralyzed.

This did not put a dent in the prodigy’s focus on the “fiddle,” however. Then, as now, he plays sitting down. The rest of the time he walks with crutches or drives around on an electric scooter. It is for this reason that he performs at benefit concerts for the eradication of polio and for people with disabilities.

At five, Perlman began studying at Tel Aviv’s Shulamit Academy of Music, and by the age of 10 was performing in recitals. In 1958, when he was 13, his parents moved to New York City so that he could study at Juilliard, where he won a scholarship. A mere six years later, he debuted at Carnegie Hall.

He first became known by a foreign audience in 1959, when he performed on Ed Sullivan’s Caravan of Stars, a TV talent show featuring young artists.

Nurturing young talent

His meteoric career as a soloist, a conductor of the world’s leading orchestras and eclectic player of classical, jazz, film-score and klezmer music (using one of the finest Stradivarius violins, formerly owned by the late Yehudi Menuhin), has not waned since then.

Nor has his passion for cultivating fresh young talent, which he does through his teaching at Juilliard and the PMP.

“Mr. P. is unique in that he encourages students to be individual artists. And he keeps in them involved in the discussion about what they play and how they play,” says a PMP participant who studied with Perlman at Juilliard and PMP.

“Here in Israel, we saw an example of this, when some of our violinists played the same piece on different nights. Each was completely different, but equally fantastic.”

Toby Perlman, with whom the maestro has five children (three classical musicians, a rock musician and a lawyer) and eight grandchildren, concurs.

“The trick is to know when to shut up,” she says, referring to her husband’s ability to let gifted young musicians express themselves without being made to feel self-conscious “about playing Mozart like Brahms.”

Asked whether anything was missing from his early training, Perlman pauses. His wife jumps in to provide an unexpected answer.

“What he missed growing up was going to high school,” she says. “Once he got to New York, he was home-schooled. I think anybody who does that misses out on the socialization process, which is important for getting along in the world. You have to learn about authority, about boundaries, about getting your homework in on time. You have to be a part of the society. Even though he’s done okay in life, this aspect is something that’s hard to catch up on.”

Perlman listens while she speaks, slightly grinning. And then he brings the conversation back to his comfort zone – music.

“Much of what a musician becomes is not about what he learns at 18,” he says. “But what he continues to learn at 30, 40, 50 and so on. The important thing is to grow, not stand still, and never feel that it’s boring. There always has to be a freshness to it. The key is always to be satisfied musically. And I don’t know if that’s something you can study.”