When Google announced in the summer of 2007 that it was holding an X-Prize competition to land a robotic spacecraft on the moon, private groups across the world scrambled to raise the $50,000 entry fee.

Right before the cutoff date at the end of 2010, three young Israeli engineers — Yariv Bash, Kfir Damari and Yonatan Winetraub — decided to join the other 33 groups that had already signed up, as ISRAEL21c reported in 2011.

Their vision was not only technological; it involved a sense of national pride, as well. They felt that Israelis, famous for innovation and ingenuity, could not pass up the opportunity to take part in such an endeavor.

Hence, SpaceIL (“IL” for Israel) was chosen as the name not only for this specific project, but for the nonprofit organization they established for a broader educational goal of encouraging young Israelis to take an interest in science and technology.

Nor was their ambition connected to the prize money. Though $30 million might sound like a lot of cash, it will cost $30 million to $100 million to create the smallest and most commercially viable craft to date.

“It was a combination of Google’s aim and the passion of the core team that enabled it to enlist every relevant sponsor in the country,” CEO Eran Privman tells ISRAEL21c at the SpaceIL headquarters in donated offices at Tel Aviv University.

Yitzhak Ben-Israel, head of the Israel Space Agency (ISA), immediately gave his blessing. More importantly, says Privman: “He helped open crucial doors, and has been accompanying us on the project to this day, including with a financial contribution.”

X-Prize, the foundation managing the contest, requires applicants to be privately funded (only up to 10 percent of the total cost may come from governmental sources), and to meet specific goals – such as the ability to land the unmanned vehicle on the moon, move it 500 meters and take photographs and video from all angles.

Pitching in to reach the moon

Ben-Israel provided the team with the international connections it needed to purchase launchers, since the only countries that have them are the United States, Russia, China and France.

And because of the ISA, Privman says: “We were able to get the backing of Israel Aircraft Industries, which has donated many hours of engineering and technological know-how.”

The Weizmann Institute of Science and many private industries “flew” into action to help. Software companies donated software and development support; hardware companies provided cameras meeting the unique requirements for remaining intact in space.

All the equipment the team needs for launching the robot into space must be tested thoroughly and built to withstand radiation and extreme cold and hot temperatures. This is another expensive aspect of the program.

So far, SpaceIL has managed to raise $20 million of the $35 million goal it has set for the project. Its chief donor is Amdocs founder and Israeli high-tech giant Morris Kahn. Bezeq gave $500,000. Donations range from seven-figure sums to checks for NIS 18.

“Compared to our competitors, we are the best-funded at this stage,” says Privman.

This is not the only reason that SpaceIL — with 20 full-time staff members and more than 250 volunteers — is considered, even by NASA, to be a frontrunner in the challenge.

Smallest, smartest spacecraft

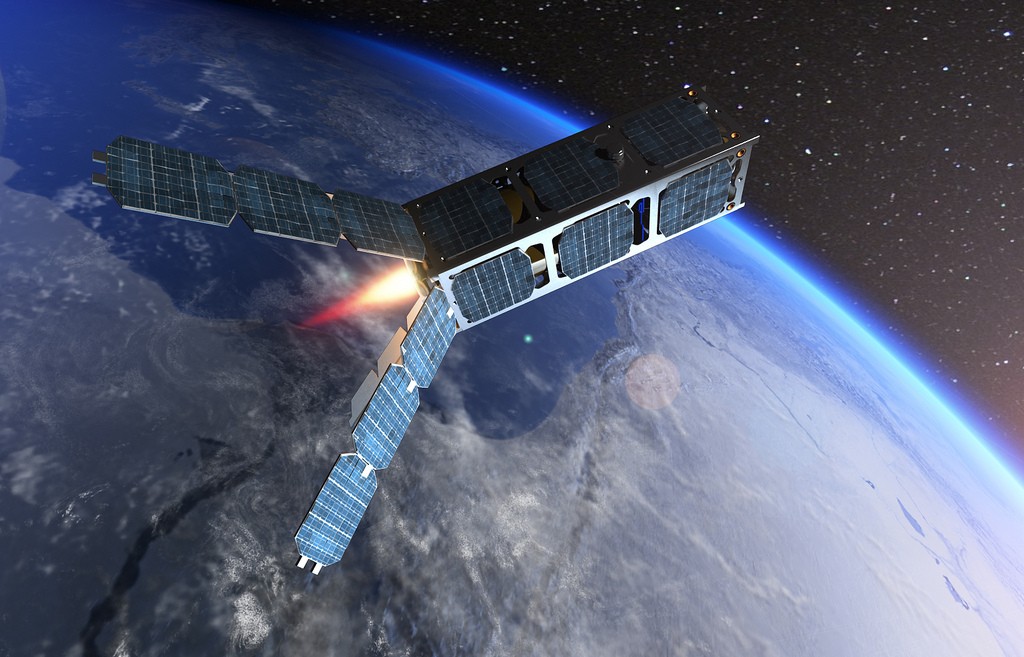

Israel’s aerospace industry has a distinct advantage because of its innovation in micro- and nano-satellites. SpaceIL is now applying this technology to build the “smallest, smartest spacecraft ever to have landed on the moon.”

The size of an American dishwasher, the SpaceIL spacecraft weighs a mere 140 kilos, 80 percent of which is fuel. It is one quarter of the size of the spacecrafts of the other competitors.

Although it will be largely preprogrammed, the craft will be remotely controlled via a control center in Yehud, not far from Tel Aviv. The team invented a special navigation method for the mission, using the stars and the moon surface as guidance points.

Other technology being developed, with the help of Israeli startups, involves the cameras, which cannot weigh more than 200 grams, and the satellite communication system for sending photos back to Earth.

“If we can’t transmit the pictures,” explains Privman, “It will be as though none were taken.”

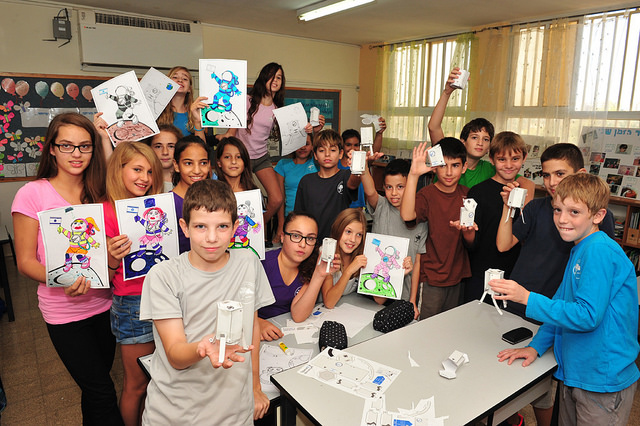

After the launch is completed, probably by the end of 2015, scores of volunteers plan to share the SpaceIL story with children in Israeli classrooms.

“The response has been phenomenal,” says Privman.

The Ramon Foundation, headed by Rona Ramon — the widow of Israel’s first astronaut, Ilan Ramon, who was killed in the 2003 Columbia space shuttle disaster — is one of SpaceIL’s many educational partners.

In addition, SpaceIL partners with the Chicago-based iCenter (a partner in iMMERSE with ISRAEL21c) and other US groups to present the program to Jewish communities, day schools and youth movements in the Diaspora, to show them what Privman calls a “different and exciting angle of Israel. It is a social business model that is also a Zionist project.”

For more information, see http://www.spaceil.com/.