Ever notice how a spilled drop of coffee spreads into a ring stain on your shirt? The particle-filled liquid flows outward from the drop, leaving the particles on the rim of the ring as the liquid evaporates.

This phenomenon posed big problems for printers. How do you keep drops of ink in place? Then Hebrew University Prof. Shlomo Magdassi realized it could actually provide a way to move the industry toward a fantastic future in functional printing.

“Instead of solving the coffee-ring problem, I thought I could use it,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

On the university’s Givat Ram campus in Jerusalem, a company called ClearJet uses Magdassi’s patented technique to make transparent conductors by digitally printing clusters of narrow silver nanoparticles, forming “coffee rings” on plastic or glass. This is what makes the touchscreen on your smartphone possible.

“When I started to be involved in the world of digital printing, there was very little public information on how to make the inks, so I had to learn from scratch,” says Magdassi in his office at the university’s Casali Institute of Applied Chemistry.

Since 1995, he has formulated revolutionary micro-nanoparticle solutions to deliver active ingredients, whether in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals or inks.

Solar cells, architectural glass

In California’s Mojave Desert, the Israeli-US company BrightSource Energy built the world’s largest solar electricity generation installation using coatings containing nanoparticles that Magdassi and a colleague, Prof. Daniel Mandler, developed. The field’s mammoth towers are each surrounded by about 10,000 mirrors throwing sunlight at them.

The mural-like glass walls made by the Israeli company Dip-Tech, adorning buildings across the world, are based on Magdassi’s patented GlassJet, a heat-resistant digital inkjet ink made of nanoparticles of glass and inorganic pigments.

“What I do is related to basic science, but I also like to see something real coming out of it — a product on the shelf — and I was lucky to have several products go on the market based on my inventions,” says Magdassi, a pioneer in silver nano-inks for printing conductors directly on plastic or solar cells.

“It’s all about controlling the behavior of the particles, which is based on basic colloid science,” he says.

Yissum, the university’s research and development company, licensed Magdassi’s process to XJet Solar, an Israeli firm that makes nano-ink and inkjet printers for solar cells.

Magdassi is now working with Yissum to find a commercial partner to develop his new oxidation-resistant copper nano-inks for inexpensive printing of conductive patterns on heat sensitive plastic substrates.

From ma’abara to ma’abada

Remarkably, the 60-year-old scientist’s life trajectory has taken him from ma’abara (transit camp) to ma’abada (laboratory).

His parents emigrated from Iraq in 1951, married and settled into one of the hardscrabble transit camps set up for new immigrants in Ramle, not far from today’s Ben-Gurion International Airport.

Though his home lacked material comforts, his education propelled him to become the first of his family to earn a doctorate. “I knew when I was in fifth grade I was going to be a chemist, while conducting experiments at home,” Magdassi says.

After serving in the army, Magdassi went to the Hebrew University and never left, aside from an 18-month post-doc in Ohio and a sabbatical in Los Angeles, during which he developed nanoparticle drugs.

His wife, Tsila, is deputy director of school psychological services for Jerusalem. Their son, 27, is studying industrial design at the renowned Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. Their 23-year-old daughter, recently back in Israel after a post-army trip around the world and volunteering in Uganda, will study law and social work at the Hebrew University next fall.

Let there be light

Magdassi’s students readied a few dazzling demos for the fourth International Nanotechnology Conference and Exhibition (NanoIsrael) conference on March 24 and 25 in Tel Aviv.

Among the printed electronics they fashioned are electro-luminescent devices imprinted with transparent conductors – in other words, a lamp illuminated by nanoparticles.

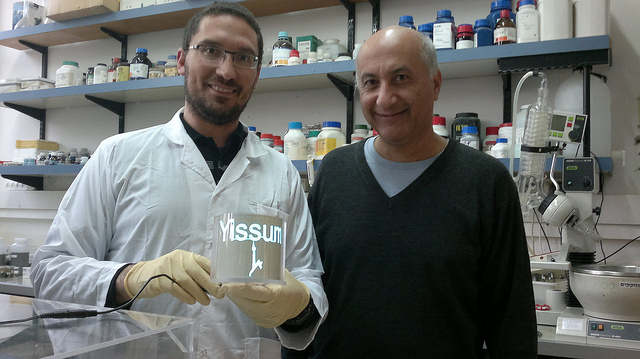

“Using our inks, you could have signage without light bulbs, and sensors of all kinds,” says Magdassi as his master’s student Alon Shimoni plugs in a glass panel on which the word “Yissum” lights up. “You can print contactless credit cards, solar cells and RFID [radiofrequency identification] tags, which are a type of antenna.

“It’s all related to how we make a small particle and put it on a substrate exactly where we need it. Then we use its specific property to get something out of it.”

Silver has long been known as an excellent and stable conductor, but at $700 to $1,000 per kilogram, it’s not practical for mass ink manufacturing. Copper, less than $7 per kilo, has similar conductivity but not stability, as it oxidizes quickly on contact with air.

Magdassi hit on the unique idea of using copper precursors of the metal, because they do not oxidize.

“Once we put it on a substrate and heat it to a certain temperature, it decomposes and makes a self-reduction, meaning it converts into copper and it becomes conductive,” says Magdassi. “The copper nanoparticles are formed from the precursor and therefore it’s stable.”

Yissum CEO Yaacov Michlin noted that the total market for printed, organic and flexible electronics is projected to grow from approximately $16 billion in 2013 to $76.8 billion in the next 10 years.

“The copper-based nano-ink invented by Prof. Magdassi solves some of the major limitations that are preventing widespread use of conductive inks, and we are certain that this novel ink will become an important aspect of the growing industry of printed electronics,” Michlin said.