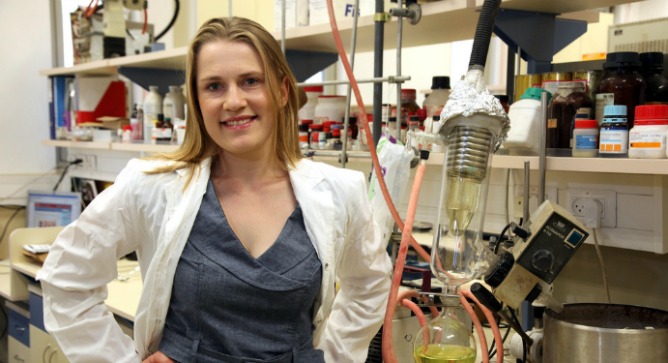

Lital Magid didn’t set out to become an award-winning medicinal chemist at Hebrew University’s School of Pharmacy. She had no idea how to say “chemistry” in Hebrew, let alone English, when she immigrated with her parents to Jerusalem from Russia at age 13 in 1992. And she had no interest in science.

“The only interest I had was to go back to Russia,” she tells ISRAEL21c with a laugh. “It was really hard for me. I knew about two words in Hebrew.”

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

She finally blossomed after starting ORT Ramot high school in Jerusalem the following year, diligently mastering both Hebrew and English. Along the way, she fell in love with the Israeli people and lifestyle. “I felt very secure here in a way I couldn’t feel in Russia,” she says.

Her youthful tenacity has paid off professionally, too. Trained as a registered nurse by the Israeli army and having earned her bachelor’s in nursing at Tel Aviv University, Magid decided she would prefer “real science” and labored to catch up with other organic chemistry students at Hebrew University so she could go right into a master’s degree program.

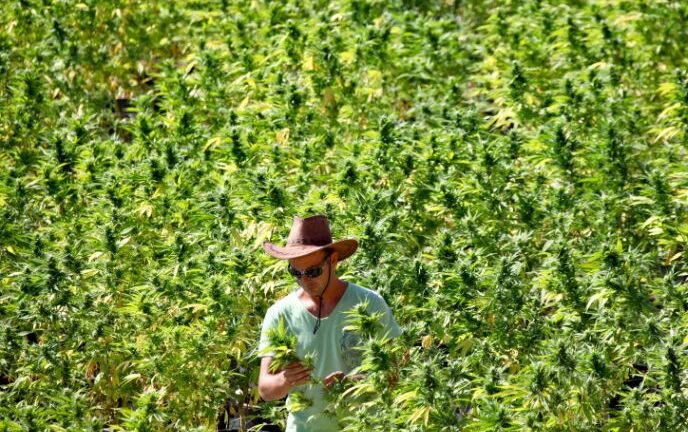

The university recently gave Magid a Kaye Innovation Award for synthesizing 22 versions of the cannabinoid THC – an organic substance in the marijuana plant that has great potential for treating neurological and inflammatory diseases. She was mentored by the global pioneer of this field, Prof. Raphael Mechoulam.

“I was an only child and was brought up to be very independent,” says Magid. “I was always expected to be efficient at everything in life.”

‘Little Girl’ makes a big discovery

True to that expectation, Magid says she was a good nurse. However, she had gone into nursing at the urging of her mother, and her heart wasn’t in it. She really wanted to be in a laboratory — Mechoulam’s lab, to be specific.

She’d heard that Mechoulam encouraged his graduate students to work independently and express their own thoughts and ideas. When she first approached him, his lab was full, so she waited patiently for an opening.

For the first year and a half, her mentor playfully called her “Little Girl,” a takeoff on “Lital” that didn’t bother her a bit.

“It was okay with me — he was the age of my grandfather,” explains Magid.

And he certainly didn’t treat her like a little girl. Mechoulam introduced Magid to the molecule that would become the focus of her award-winning work.

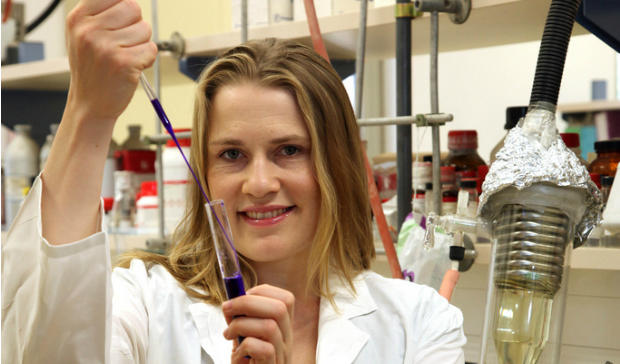

Mechoulam had shown that THC binds to a brain receptor called CB2. That’s significant, because cannabinoids also bind to the CB1 receptor responsible for the psychoactive effects of marijuana. CB2 doesn’t trigger those effects, but it kick-starts therapeutic properties such as relief from pain and other symptoms of disease.

Magid’s job was to synthesize the molecule for more widespread application. After months of hard work and advice from pharmaceutical chemistry professor Morris Srebnik, she succeeded. By now she has 22 cannabinoid compounds to her credit.

‘I didn’t want to leave my work’

Her early success spurred her on to complete a doctorate.

“I didn’t have plans for a PhD, but I didn’t want to leave my work – I wanted to see the effect of my molecules in biological models, and synthesize derivatives,” she says.

Mechoulam allowed her to stay on, and invited her to test her compounds in animal models although her background was not in biology. She eagerly accepted.

“This receptor, CB2, plays many functional roles in the immune system and the central nervous system,” she says. “I really want to cure the world from multiple sclerosis. I believe CB2 can be over-expressed in this disease, and if one of my compounds can bind to the receptor it can improve the functional status of the patient.”

Working with psychopharmacology professor Esther Shohami, Magid saw good results in 2008 with her experiments involving anti-inflammatory effects of her compounds, which have since been patented through the university’s Yissum tech transfer company and licensed to a major pharmaceutical company.

“I thought nothing would come of the patent, but interest in CB2 suddenly grew and everybody wanted to search in this direction for therapeutics,” says Magid, who overcame her fear of public speaking in English so that she could present at international conferences in the cannabinoid field.

Her agents are closer to THC than others synthesized in labs elsewhere. “We believe if you have a compound similar in structure to marijuana, it won’t be as toxic as other synthesized compounds for activating CB2 can be,” she explains. “If you stay close to nature, then probably the human body won’t reject it.”

While waiting for the slow wheels of drug development to turn, she is doing further experiments.

Magid is married to a physical therapist and lives in Jerusalem. After giving birth to a daughter and son, now four years old and 18 months old respectively, she began leaving the lab at 4:00 every afternoon.

“I used to stay there without limit — even overnight if I wanted to. But I learned to manage with the children and the research. I say to all my friends that my research is one project and I have another two projects at home,” says Magid.