Anyone who has worked the night shift knows that a lot of snacking takes place in order to keep awake. That’s because many biological processes follow a set timetable, with levels of activity rising and dipping at certain times of the day. Such fluctuations, known as circadian rhythms, are driven by internal “body clocks” based on an approximately 24-hour period – synchronized to light-dark cycles and other cues in an organism’s environment. Disruption to this optimum timing system in both animal models and in humans can cause imbalances, leading to such diseases as obesity, metabolic syndrome and fatty liver.

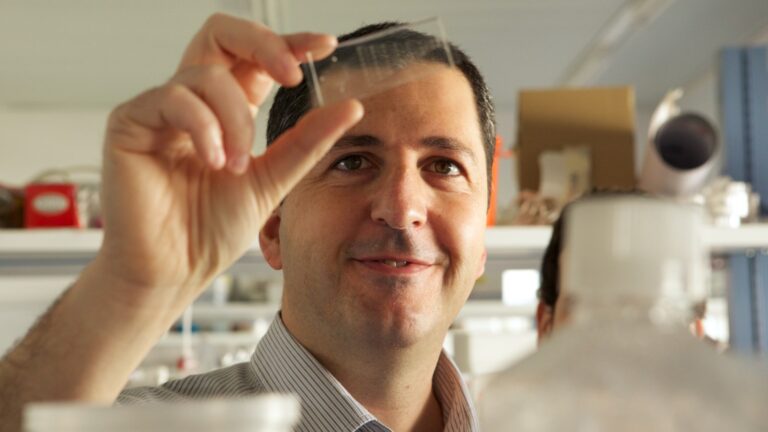

Postdoctoral fellow Yaarit Adamovich and the team in the lab of Dr. Gad Asher of the Weizmann Institute’s Biological Chemistry Department, together with scientists from Dr. Xianlin Han’s lab in the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute in Orlando, studied the role of circadian rhythm in the accumulation of lipids in the liver in mice.

They discovered that a certain group of lipids, namely the triglycerides (TAG), exhibit circadian behavior, with levels peaking about eight hours after sunrise. The scientists were astonished to find, however, that daily fluctuations in this group of lipids persist even in mice lacking a functional biological clock, albeit with levels cresting at a completely different time – 12 hours later than the natural schedule.

“These results came as a complete surprise: One would expect that if the inherent clock mechanism is ‘dead,’ TAG could not accumulate in a time-dependent fashion,” says Adamovich.

So what was making the fluctuating lipid levels “tick” if not the clocks? “One thing that came to mind was that, since food is a major source of lipids – particularly TAG – the eating habits of these mice might play a role,” she says.

Usually, mice consume 20 percent of their food during the day and 80% at night. However, in mice lacking a functional clock, the team noted that they ingest food constantly throughout the day. This observation excluded the possibility that food is responsible for the fluctuating patterns seen in TAG levels in these mice.

When the scientists proceeded to check the effect of an imposed feeding regimen upon wild type mice, however, they were in for another surprise: After they provided the same amount of food – but restricted 100% of the feeding to nighttime hours – the team observed a dramatic 50% decrease in overall liver TAG levels.

“The striking outcome of restricted nighttime feeding – lowering liver TAG levels in the very short time period of 10 days in the mice – is of clinical importance,” says Asher. “Hyperlipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia are common diseases characterized by abnormally elevated levels of lipids in blood and liver cells, which lead to fatty liver and other metabolic diseases. Yet no currently available drugs have been shown to change lipid accumulation as efficiently and drastically as simply adjusting meal time – not to mention the possible side effects that may be associated with such drugs.”