When you have a fever, your nose is stuffed and your body aches from head to toe, you are getting a message to stay home in bed — not just to rest but to ensure the survival of the species, according to an Israeli study.

“Sickness behavior” symptoms such as fatigue, depression, irritability, discomfort, pain, nausea, and loss of interest in eating and sex may be an evolutionary adaptation pushing us to isolate ourselves while we are contagious.

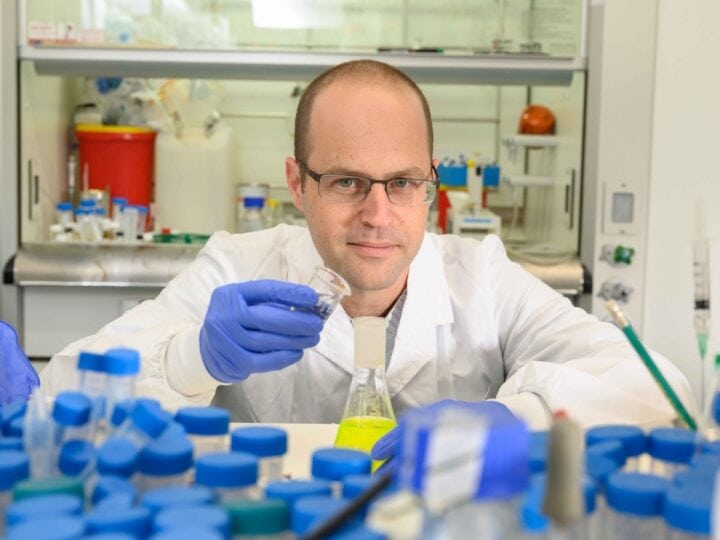

“We know that isolation is the most efficient way to stop a transmissible disease from spreading,” said Weizmann Institute of Science senior immunology researcher Guy Shakhar, author of the study with Keren Shakhar of the psychology department at the College of Management Academic Studies in Rishon LeZion.

“The problem is that today, for example, with flu, many do not realize how deadly it can be. So they go against their natural instincts, take a pill to reduce pain and fever and go to work, where the chance of infecting others is much higher.”

The Shakhars believe that psychological symptoms of feeling sick are not produced directly from the pathogen that triggers physical symptoms such as fever and anemia, but rather are “orchestrated by the host’s immune and neuroendocrine systems.”

In an article about their hypothesis published last October in PLoS Biology titled “Why Do We Feel Sick When Infected—Can Altruism Play a Role?” the researchers suggest that mammals have evolved several parallel pathways to alert the brain of inflammation and trigger symptomatic behaviors.

Symptoms discourage contact

The scientists describe how common symptoms of illness seem to support the hypothesis that their purpose is to keep us away from others.

Appetite loss, for example, hinders the disease from spreading by communal food or water resources. Fatigue and weakness can lessen the mobility of the infected individual, reducing the radius of possible infection. Decreased interest in social and sexual contact also limits opportunities to transmit pathogens. And lapses in personal grooming and changes in body language say: “I’m sick! Don’t come near!”

The idea that sickness behavior reduces transmission has been proposed before, but was never recognized as a major organizing principle in vertebrates, the authors say.

“We name this theory ‘the Eyam hypothesis’ after the English mining community that isolated itself to contain an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1666. Three-quarters of the villagers reportedly died, but the surrounding communities were saved,” they write.

The scientists have proposed several ways of testing their hypothesis. In the meantime, they urge all of us to take the hint from our bodies and stay home when we feel ill.

They point out that sickness behavior can be observed in such social insects as bees, which typically abandon the hive to die elsewhere when they are sick.

“In animals, such changes can be quantified based on behavior and reflect reprioritization of motivations during disease,” they write.

Whether or not the individual person or animal survives the illness, isolation from the social environment will reduce the overall rate of infection in the group.

They believe this reprioritization is the task of a specialized gene. “From the point of view of the individual, this behavior may seem overly altruistic,” said Keren Shakhar, “but from the perspective of the gene, its odds of being passed down are improved.”